How did decentralisation policies affect Central African Republic's struggling education sector?

The Central African Republic’s government decided to undertake wide-ranging state reforms in the 1990s, including a rewrite to the constitution to restructure strategic activities for the country’s development. While problems persist, the education sector has had much to gain from the introduction of decentralisation policies.

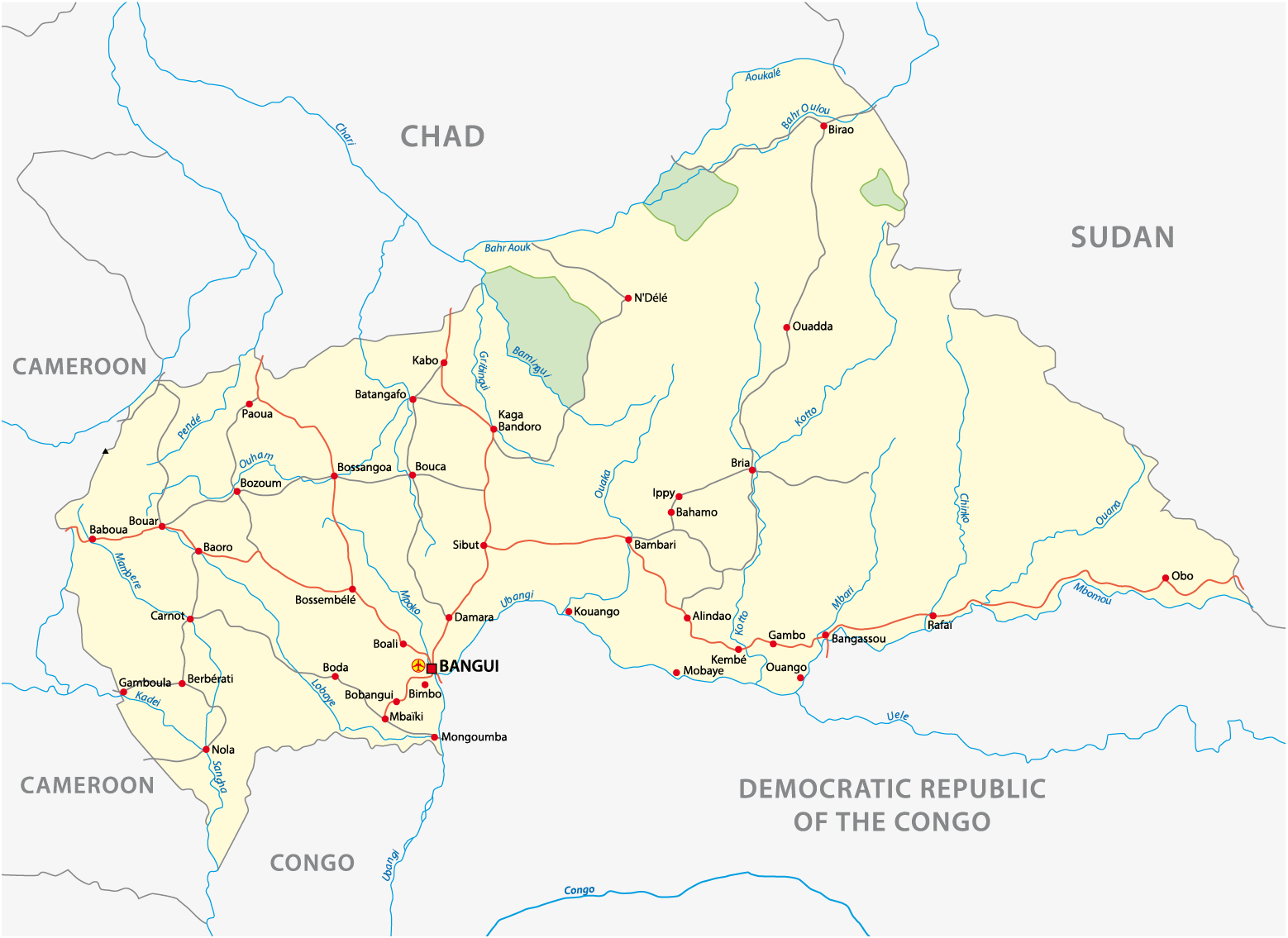

The Central African Republic is a landlocked country in Central Africa, with a population of 4.66 million people

“To decentralise means to bring the administration closer to the beneficiaries,” said Jonas Guezewane. “The beneficiaries are the citizens – who don’t only live in the big towns. They are spread across the territory.”

Guezewane is an education specialist, who used to be a coordinator with the Sectoral Committee of Education in the Central African Republic. Since the 1990s, he has watched the country’s education sector become progressively decentralised.

The Central African Republic published its new constitution in 1994, giving a strong emphasis to the decentralisation of the country’s administration and placing decision-making processes – both political and financial ones – in the hands of seven administrative regions and sixteen prefectures.

Decentralisation has come with its share of challenges, though.

Problems in transition

The country’s government divided the state into prefects, sub-prefects, and communes, with authority delegated to each; the French system served as model for this undertaking.

As relatively independent regions were grouped together, resentment at new dependences caused administrative blockages. “In practice, we found ourselves not in a state of decentralisation, but more in a state of deconcentration,” explained Guezewane.

What is deconcentration?

Often considered the weakest form of decentralisation, deconcentration redistributes decision making authority and financial and management responsibilities among different levels of the central government.

The process can result in a shift of responsibilities from central government officials in the capital city to those working in regions, provinces or districts, or it can create strong field administration or local administrative capacity under the supervision of central government ministries.

For more visit CIESIN.org

According to Guezewane, financing has remained a central issue, causing some regional authorities to be unable to back sectoral development efforts.

“Decentralisation shouldn’t be a way of discounting a whole culture”

Because of disputes on the allocation of funds, there is now a push to revaluate the composition of the regions – and their number – in order to structure the administrative divides in a more equitable manner.

The prefecture of Ouaka serves as example. More populous, but also more spread out than the neighbouring Kémo, the people of Ouaka were proud to be part of the largest prefecture. Under the new system, however, Ouaka and Kémo were grouped.

“It would have been better for them to keep their authority, their size, and for decentralisation to be accompanied by infrastructure works,” said Guezewane. “Decentralisation shouldn’t be a way of discounting a whole culture… it should allow for the development of local communities.”

Gains despite disputes

The Central African Republic’s educational system dates back to the period of colonisation, with the number of educational academies corresponding to the size of the student-aged population.

But while there are seven administrative regions, eight academic divisions were created. “And how to fit these eight academic divisions into seven,” Guezewane asked. “This is a problem which we still haven’t been able to resolve.”

Despite this, the educational sector has seen very real gains from the decentralisation and deconcentration processes.

Decentralisation in education has brought the administrators closer to the intended beneficiaries, said Guezewane © Pierre Holtz/UNICEF

“The decentralisation of the educational services provided real advantages,” Guezewane said. “First and foremost, the scholastic administration was brought closer to its intended beneficiaries.”

This new-found proximity has improved class attendance and the furnishing of classrooms, Guezewane said.

Decentralisation means that desks and chairs are sourced locally, saving time and money, as furniture previously needed to be both signed off on and sourced from the capital.

But, more importantly, decentralisation has brought the voice of community members into the decision on how education is managed.

Jonas Guezewane on the benefits of decentralisation for the Central African Republic's education sector (in French, with English subtitles):

From communal leaders to parents and students, this increased ownership of the process has meant that people feel responsible for and take pride in the schools. “This means that when the school year starts, the teachers are already there, and have a classroom to teach in,” said Guezewane.

Decentralisation has ensured that primary schools are built in villages where the students actually are – meaning attendance rates have increased. High schools, however, have remained at the prefecture level, which youth in remote villages still have trouble accessing.

School budgeting has also improved. In addition to deciding where schools are built, local authorities have also been made responsible for the budget – though they can request additional money from the government to cover gaps. Until then, the authorities in the capital, Guezewane said, “didn’t know the realities of the field, and this caused serious problems”.

School inspections have become more effective under decentralisation as well, since the inspectors no longer need to travel to the capital for financing. Working hours for teachers and inspectors have also increased, matched to lower rates of absenteeism for both.

The poor quality of roads in the Central African Republic means many teachers and administrators cannot access schools without specialised off-road vehicles © Pierre Holtz/UNICEF

“When I was an inspector, we had to identify the real problems,” Guezewane said. “The academic inspector for the Mambéré region, who was based 750 km from Bangui, didn’t have a vehicle.

“We decided to find him one that could go off-road, which allowed him to supervise the schools. For the district heads who couldn’t access the school, we got them motocross bikes. This was needed because the roads were so bad.”

Implications on teaching quality

Overall, Guezemane explained, “decentralisation provides the opportunity for reflection. To ensure that through our means – combined with the support of international partners – we reach the most vulnerable populations. That our help actually reaches the end recipient.”

“Decentralisation provides the opportunity for reflection”

Even with the decentralisation efforts, however across the country, specialised institutions for different school levels still serve to train teachers from the different academic regions. This ensures pedagogical consistency on a national level.

For primary school training, for instance, there are two école normale d'instituteurs: one in Bangui and the other in Ouaka. For a secondary school training there is less choice – with the école normale supérieure in the capital Bangui as the only option.

The problem in the past, explained Guezewane, could be found in the way the teachers were deployed, with some regions going largely unstaffed. This has been circumvented through limiting the number of teaching positions at each academy.

“There are only a few professorships in Bangui. If you want to work there, you will have to fight for it. It’s only the best who are recruited,” said Guezewane.

“However, in the real country – far to the north, on the border with Chad – we need teachers and there are hundreds of posts. The decision is clear. Either you’re unemployed, or you chose to work.”

In the north of the country, schools lack enough teachers to fill the post, said Guezewane © Eskinder Debebe/UN Photo

To work in the provinces, teachers are required to pass a regional examination in addition to their formalised training through the academies.

Once they pass, they must stay at their posting for at least five years before they are able to apply for inter-academic movements, incentivising attendance in the localities while providing for longer term career development.

Innovative solutions can complement decentralisation, explained Guezewane. A new policy put in place in Bangui through French cooperation has brought e-readers to teachers.

For teachers in the country who don’t have access to many resources, this means that documents can be loaded directly on to the tablets, which teachers can recharge in their villages with solar power.

Looking ahead

“What I’d like above all would be for development partners to keep supporting decentralisation policies, because it has clear advantages,” said Guezewane.

Prior to the European Commission (EC) taking an interested in the Central African Republic’s educational sector in 2012, only limited development aid was being provided to the country.

“We need to – at the least – be doing the minimum, so that schools can bring change”

While France was involved in traditional development programmes, the EC has since provided two rounds of budget support to address political problems and internal debt. The educational sector has had much to gain from these.

A focus on improving access rates, schooling rates, recruitment and parity, especially in regions in difficulty, all quantified through indicators, left a mark. “There are localities that didn’t have a school… these new policies gave us the means of going directly into those regions,” said Guezewane.

“Talking to other development practitioners in education, I see that decentralisation is a question that preoccupies everyone. There are many ingredients that need to be brought together for quality to be achieved in education. From proper furnishing, to teachers, to the right material, we need to - at the least - be doing the minimum, so that schools can bring change and function as real places of learning.”

This article was written by Craig Hill.

Log in with your EU Login account to post or comment on the platform.