If you have ever been to Honduras, you will know that it is one of the greenest countries in Central America. Forestry has had a long history there and continues to be an important source of energy for the impoverished rural population, as well as maintaining a biologically diverse ecosystem. Over 50 percent of the country is covered in forests, which are also home to indigenous peoples.

These forests also protect highly vulnerable water sources, and act as a natural barrier against landslides, as well as mitigating other natural disasters that often affect the region.

Unfortunately the country suffers from serious deforestation. A report from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change states that globally agriculture is the main driver of deforestation: primarily subsistence farming, followed by commercial agriculture. Wood extraction – both for commercial and fuel purposes – is the other key driver, but it accounts for significantly less deforestation.

Forest owner Carmen Borjas claims that illegal activities have pushed small-scale owners out of the local market. “Illegal actors don’t pay taxes,” she said, which means they are able to charge lower prices. With more and more people buying illegal timber, it is difficult for small-scale owners to cover production costs and compete fairly in the market.

Partnerships between the EU and Honduras not only help tackle illegal logging, but also drive sustainable development. This is where Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) plays a crucial role.

The EU's FLEGT Action Plan was established in 2003. It aims to reduce illegal logging by strengthening sustainable and proper forest management. The initiative also aims to improve governance and promote legally produced timber.

FLEGT Regulation allows the European Commission to negotiate bilateral trade deals called Voluntary Partnership Agreements (VPA) with timber-exporting countries. Under a VPA, the partner country agrees to, at the very least, export legal timber products to the EU. In return the EU agrees to give verified legal timber products automatic access to its market. Once an agreement is reached, all wood products can be purchased by buyers in the EU, with the knowledge that they are legal under the VPA framework.

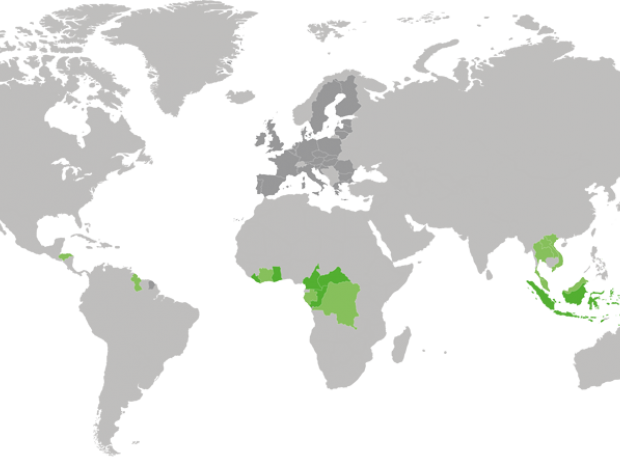

Six countries are currently implementing a VPA – Cameroon, Central African Republic, Ghana, Liberia, Indonesia and the Republic of Congo.

VPA countries Credit: EU FLEGT Facility

VPA countries Credit: EU FLEGT Facility

Nine other countries are still negotiating with the EU, including Honduras. It is the first country in Central America to start VPA negotiations. Representatives of the Honduras Government, private sector, civil society and indigenous people met EU representatives in October 2015 in Brussels for the fourth round of negotiations.

This was the first time that the voices of indigenous people from Honduras were heard at the European level in the framework of the FLEGT Action Plan.

“These negotiations are a good example whereby civil society and indigenous groups are taken into consideration,” said Solomon Ioannou, a Cooperation Officer from the EU Delegation to Honduras. “What they are seeking, is that the safety of their territory and the application of law are guaranteed.” This is important, he explained, for issues such as land rights, to allow indigenous groups to better define and exercise their rights as property owners. This doesn’t just mean establishing a geographical area where they have rights as indigenous groups, elaborated Ioannou, but also having the governance rights to manage the commercial use of their lands.

Voluntary Partnership Agreements are also seen by the Honduras government as a way for the country to develop.

“The signature of the Voluntary Agreement with the European Union is, for us, a great opportunity,” said José Antonio Galdámes Fuentes, the Minister of Environment of Honduras.

“The use of the forests in Honduras is very important for development,” Galdámes continued. “[Forest users] will follow the legislation, respect the human rights and also make sure that we don’t lose our natural resources.”

During the meeting the Minister also said that “a transparent environment, with transparent governance of the forest sector, would also attract foreign investors. This would contribute to the reduction of poverty in the communities, where the forest helps people to meet their daily needs.”

The negotiations were also important for the timber industry. In the long-term the VPA will open doors for forest owners increasing the export of wood from Honduras to Europe. For now the negotiations offered them the chance to openly engage with the government, expressing their concerns.

“There are external actors, in this case it is the European Union, that are making our government see that it is hindering the development of the industry,” said Carlos Garcia from the Honduras Association of Timber. “That is why it is positive that we are participating in these kinds of negotiations.”

Small forest owners also see the negotiations as an opportunity.

“If governance improves, then all the programmes and projects that are targeted at improving governance in Honduras, will help small owners have better access [to the market], to make the selling of the wood easier,” said Borjas.

But representatives of civil society and indigenous groups have expressed some concern about the VPA process in Honduras.

“One of the biggest challenges that we had when talking about the development was the inclusion of the gender perspective in the VPA process,” said Glenda Rodriguez from Progressio Latina, a Civil Society Organisation.

“The women are involved in 90 percent of the forest activities. The only part they don’t participate in is the logging,” she continued.

“We have consulted women and we now understand their situation. Nevertheless it was not always very clear to see those concerns reflected in the legal definitions, criteria and annexes of the VPA,” Rodriguez said.

Even before the VPA negotiations on FLEGT started between the EU and Honduras, the country had started to make progress in its efforts to eliminate illegal logging. The Latin American country passed a forest law in 2007 and a national strategy against illegal logging in 2010. In 2014, the overall imports of wood products from Honduras to Europe rose by 12.4%, according to Global Trade Atlas.

The growing partnership between the EU and Honduras has already brought benefits.” It’s interesting to see how budget support can assist in the implementation of good forest governance,” said Ioannou.

“The country has already used budget support funds to help restore forests from the outbreak of the pine beetle plague,” he added.

The VPA is expected to be signed in 2016. Honduras still has a long way to go to in its fight against illegal logging. But there are strong hopes that the agreement will help to improve the situation.

| For further reading, please visit: |

This collaborative piece was drafted by Ewelina Kawczynska with input from Bart Missinne and Solomon Ioannou, with support from the capacity4dev.eu Coordination Team.

Comments (1)

Log in with your EU Login account to post or comment on the platform.

Since 2013, the MaderaVerde Foundation (FMV) leads the Governance Platforms (PG) in Atlántida and Colón, in its participation in the AVA-FLEGT process, promoting collaborative initiatives to face the challenges experienced in the forestry sector, especially by community-based organizations that constitute them. Now we are glad to conclude successfully our second project financed by the FAO-UE FLEGT Program: "Strengthening advocacy capacities in the Atlántida and Colon Governance Platforms, for the implementation of a viable VPA for all".

After six years, the VPA of Honduras is signed and we applaud the very participatory process that supports it. However, according to the last official data of the Forest Conservation Institute (ICF), the country's annual deforestation rate is 23,304 hectares, of which more than 17,000 correspond to our territory of broadleaf moist forests, the highest average in comparison to the portion of pine forest and other ecosystems. Certainly, after six years we cannot count any concrete action of LAW ENFORCEMENT in our territories, such as the implementation of control measures to stop the usurpation of community forests, incentives for the exploitation and commercialization of legal forest products, and other framed in the National Strategy against Illegal Logging ENCTI. Our hopes are fading, watching how our forests are destroyed, and trying to persuade our producers that it is still worthwhile to stay on the legal side of this story.