The Sustainable Development Goals, adopted unanimously by UN member states in September 2015, have given the international community and national governments a number of targets and principles – chief among them, to advance an “integrated approach”. But what does this mean in terms of projects, monitoring and stakeholders? Two senior officials from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) share their vision of an approach to the SDGs with the environment at its heart.

“The SDG agenda is a broad one,” said Elliott Harris, UN Assistant Secretary-General and Director of the UNEP Office in New York. Unlike the Millennium Development Goals, which mainly focused on reducing poverty in developing countries, the 17 goals for 2016-30 are “universal. All countries are expected to pursue these SDGs and all countries will benefit from them as they are achieved,” said Harris.

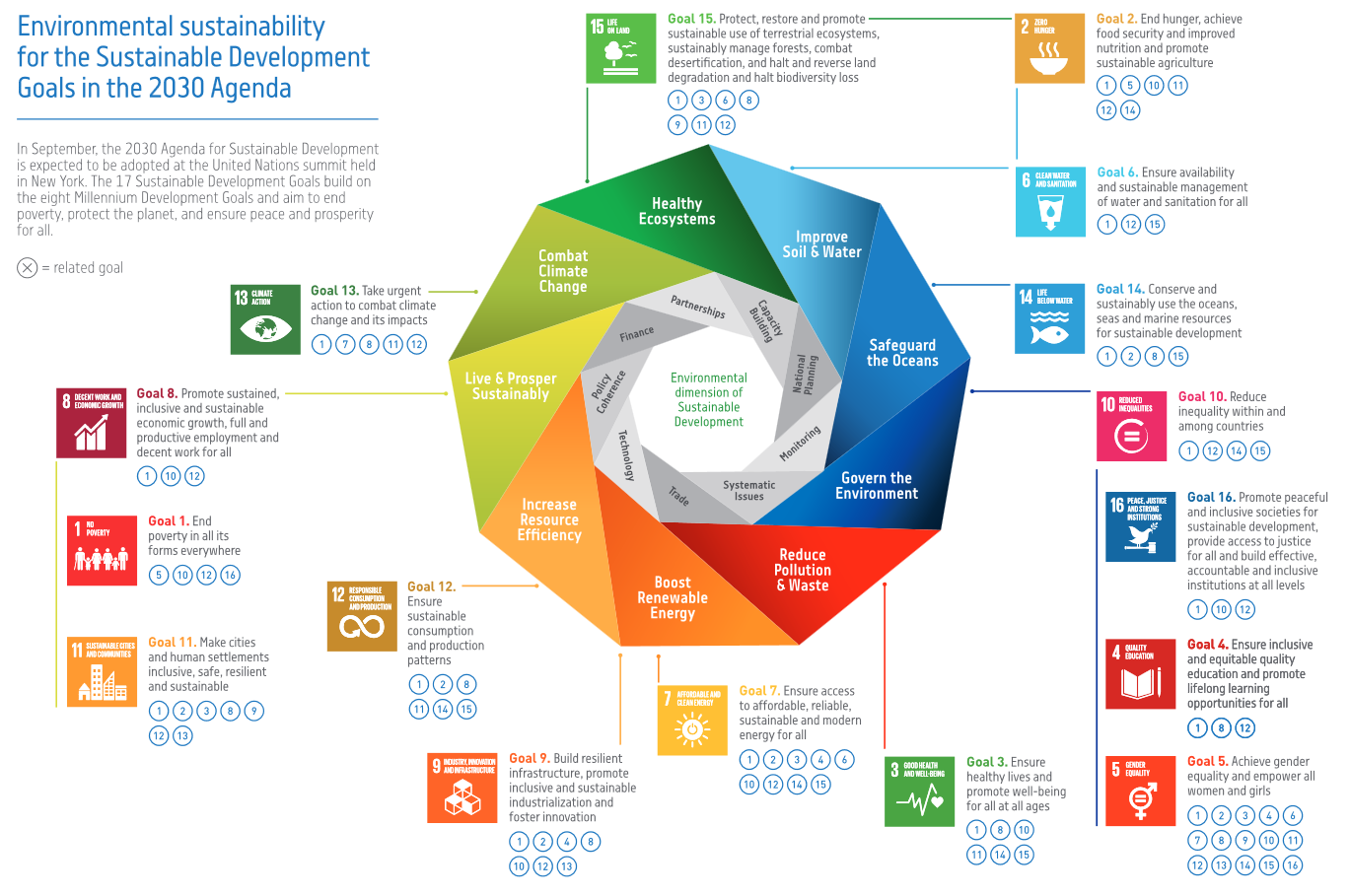

“The key point here is we are looking to pursue an integrated agenda. It’s the ability to think in terms of economic objectives, environmental objectives and social objectives, all at the same time, and to understand how progress in one area might affect progress in another area,” said Harris.

With so many moving parts, where to begin? According to Niklas Hagelberg, Senior Programme Officer at UNEP, the best starting point is the natural world, and the resources which sustain life on this planet.

“Ecosystems provide the foundation for delivering a multitude of SDGs,” said Hagelberg. Investing in smart management of ecosystems can have an impact on areas beyond the clear environmental targets concerning oceans (goal 14) and biodiversity (goal 15). In UNEP’s vision, there is an environmental underpinning to the entire 2030 Agenda, from sanitation (goal 6) to poverty reduction (goal 1), job creation (goal 8) to health (goal 3), and energy (goal 7) to inequality (goal 10).

To illustrate the interconnections, Hagelberg pointed to the well-documented example of fertiliser. Its benefits – increasing crop yields – can be outweighed by unintended consequences out of farmers’ sight. When excess nitrates from fields make their way into rivers and eventually oceans, they encourage algae to bloom, depleting oxygen in the water and killing fish. This can devastate fishermen’s livelihoods, as well as posing a health risk to the communities which rely on the water for drinking, cooking and sanitation.

The same principle applies in built-up environments, where human health is no less dependent on the natural world. Air pollution is one of the most serious environmental health risks, linked to 7 million premature deaths in 2012. Solutions lie in various fields, including investment in clean energy, better urban planning to reduce commuting, and policies which boost the use of public transport over cars.

A shift of investment – from chemical fertiliser subsidies into organic fertiliser, and from vehicle subsidies into clean transport – could have wide-reaching benefits. “These kinds of issues are prevalent in all regions,” said Hagelberg. “All countries need to take a look at the subsidies they provide to various sectors and look at the positive and negative externalities of these subsidies, both on a social and environmental level.”

“The interlinkages, these nexus issues, are particularly important,” said Harris. “Being aware of them will allow us to move towards more coherent policy formulation and better outcomes.”

|

In this context, the EU supports the Poverty-Environment Initiative (PEI) run by UNEP and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The PEI is a global programme that supports country-led efforts to incorporate pro-poor, pro-environment objectives into government policy, national development and sub-national development planning. It works at all levels, from policy-making to budgeting, implementation and monitoring. The EU also collaborates with UNEP on the The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), a global initiative focused on “making nature’s values visible”. It helps decision-makers recognise the wide range of benefits provided by ecosystems and biodiversity, demonstrate their value in economic terms and, where appropriate, capture those values in decision-making. |

The first step is finalising a policy and monitoring framework to encourage the public, private and non-profit sectors to invest, live and work sustainably.

“Most of the implementation will have to happen through partnerships, and this will pose challenges for the way we monitor what we do and the way we hold each other accountable,” said Harris.

Monitoring

To this end, a set of indicators - 229 of them, as of February 2016 – is being developed by the Inter Agency Expert Group on SDG Indicators, which will present a complete list in March. Then it will be down to member states to develop their own indicators at regional, national and sub-national levels.

A crucial step forward from the Millennium Development Goals will be monitoring across themes, by finding ways to measure various overlapping changes at once. Some of the indicators will draw on methodologies and data sets which already exist, while others will require countries to re-haul and sometimes create from scratch new data collection systems. “There is a requirement for building capacity everywhere, not just in developing countries but also in developed ones,” said Harris.

Together with official census data and information from earth observation satellites, perspectives from diverse sources on the ground are important. The spread of technology has made it possible to collect data from sources previously untapped – such as citizens with mobile phones. “Mobile telephones are powerful tools for allowing citizens on the ground affected by different issues to report on those issues,” said Harris.

For a breakdown of the targets, visit the Sustainable Development Solutions Network’s platform.

“The role of citizens is critically important,” said Harris. As well as being able to monitor SDG implementation at a local level, “Citizens are consumers, voters, they make the choices. The products we consume, the way we go about transportation, the way we consume food – these choices contribute to global warming and environmental degradation, or to reducing the impact of climate change and degradation.”

|

This is reflected in the twelfth Sustainable Development Goal on sustainable consumption and production which UNEP, with support from the EU, promotes through the SWITCH programmes in several regions, including Asia. More information on Sustainable Consumption and Production can be found at the SCP Clearinghouse. |

Engaging the private sector

Beyond the individual level, UNEP is working to show businesses and investors that it’s in their interest to engage in sustainable development. When companies have turnovers larger than national economies, their decisions have a huge impact on how natural resources are used and how ecosystems are managed.

Habits are hard to change, especially when they are incentivised by subsidies or tax breaks, as in the above case of fertiliser. UNEP is providing data and analysis to governments, which can then shape the policy environment so that sustainable projects make business sense. For more information, see the Green Economy Initiative.

“Part of the challenge will be to define the kind of projects which can be invested in by the private sector and to use government or public resources to complement and to mobilise these private funds,” said Harris.

Renewable energy is a good example of how public policy can rally the private sector and encourage investment in sustainability. Solar, wind, hydro, biomass and geothermal power projects often have higher upfront costs than conventional power projects, as well as a longer timeframe for recovering investment.

So some governments – including in Colombia - have put in place policies to encourage investment in these sectors, while channelling investors away from fossil fuels. “We’ve seen that as these policies have taken effect, the private sector has become increasingly interested in investing in renewable energy, which now offers a very competitive rate of return,” said Harris.

Examples like this are encouraging, especially if they can be re-applied to other aspects of the SDGs. “[We have] the opportunity to bring the global community together around this one set of goals and targets we’ve all agreed to in a way that’s never happened before,” said Harris. “It’s a really exciting time, and one in which we can say we’ve changed the way we think about how we live on this planet.”

Further Reading

Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform

Sustainable Development Goals: Implementation in Europe

This collaborative piece was drafted with input from Bernard Crabbe from DEVCO with support from the capacity4dev.eu Coordination Team.

Image credit: november-13 via Creative Commons

Log in with your EU Login account to post or comment on the platform.