Q&A with Rupert Simons, Chief Executive Officer of Publish What You Fund.

Publish What You Fund is a non-profit organisation that campaigns for aid transparency. “We believe that information is power and we campaign to make that information available to everyone who needs it,” said Simons. With readily available data on aid, governments and donors, citizens can ensure that initiatives are being carried out effectively. Simons (RS) spoke to Capacity4Dev (C4D) about the importance of including data collection and analysis in crisis response, as well as the next steps for making open data a standard component of development and humanitarian aid efforts.

C4D: How was the availability of data in Sierra Leone lacking during the Ebola outbreak?

RS: The [Sierra Leonean] government did not have good data but also the many donors who came into the country did not have good data, and even where they did have data, they didn’t provide any assistance to the government in how to use that data. So the result was that for the first few months of the Ebola outbreak, we didn’t know where the patients were. When we started to build hospitals, we didn’t know where the hospitals were. And even when we had the patients in the hospitals, we still needed to get the patients to the hospitals. For that we needed ambulances - we didn’t have data on either any ambulances that were in the country or who was responsible for maintaining them. So frequently half the ambulances in the country were broken down and nobody in the government knew about it. So the first problem you have is that if you don’t know where the patients are, you can’t direct the response.

The second problem you have is if you don’t know how much money is coming in, there’s no way of holding anyone accountable for the use of that money. And the third problem that you have is if you’re taking various actions to fix the Ebola problem but you don’t know the results of those actions, then you don’t know when you’ve been successful and you can continue spending money even if you’ve been successful or you’ll actually stop before you’ve succeeded.

| Click here for more information on how the EU addressed the Ebola crisis in Sierra Leone, including implementing the EU Mobile Laboratories Project and providing budget support. |

C4D: What did you do to help?

RS: At the time, I was an advisor with the Africa Governance Initiative. We built, together with a team from the government of Sierra Leone and the British military, a national situation room that became a data hub for the entire country. So what we did was every day we called all of the districts in Sierra Leone and got them to give us daily reports of the number of Ebola patients they had, where they were, and what the gaps were in service provisions - so who had a shortage of beds, a shortage of vehicles, a shortage of staff, or a shortage of funds to pay those staff.

Now as a result of collecting that data every day we were able to provide summary reports - we put those to the government decision makers. We collected the data in the morning, prepared the report in the afternoon, made decisions in the evening, the following day we repeat the cycle. You continue doing that for two or three months, eventually you get on top of the situation, and I’m glad to say that the Ebola crisis is almost solved.

But it took much longer than it had to, it cost much more money than it had to, and we lost many more lives than it had to if that data had been freely available in the first place and more importantly, people in Sierra Leone had been empowered and trained to use that data and to make decisions from it.

C4D: What is next in Sierra Leone?

RS: It’s no longer about responding to Ebola, it’s about recovering from Ebola. So that need is slightly different. You don’t need to count the number of patients every day, you don’t have patients anymore. What you need to do is track the money that’s coming into the country, see what that money is supposed to do, and make sure that those things are actually being done.

Now whether that’s the responsibility of the government or of the donors of the NGOs, the critical thing is that ordinary Sierra Leoneans have the information on what has been committed so that they can hold the government to account. The good news is, because we worked with so many young, energetic Sierra Leoneans to solve the Ebola crisis, that there are now people who are trained in how to use Excel and data management tools to do basic analysis, data collection, and reporting. That will help Sierra Leoneans with the recovery.

C4D: What is preventing open data from becoming more widely available / used?

RS: The two biggest obstacles we face are lack of political will and difficulty identifying effective demand. On the first point, we know that some funders like the Netherlands, Sweden and UNDP are publishing and using high quality data, so there is no technical problem, it’s about whether other funders make it a priority. Look at our EU aid review if you want to see who is doing well in the EU! On the second point, there is lots of demand for this data, but that demand is dispersed and inchoate, making it difficult for publishers and decision-makers to work out what people really want. One of the things we try to do at Publish What You Fund is connect publishers with data users so they can better understand and respond to each other’s needs.

| For more information on making data more widely available and the future of data in development, you can watch an interview with David McNair Policy Director for Transparency & Accountability for the ONE Campaign in the ICT & Space group. |

C4D: What is the future of open data?

RS: I think that open data is to closed reporting as Wikipedia is to a published encyclopaedia. For a while you have just the old, closed standard, then you have both running in parallel, eventually you only need the open data. We are now in a transition period in which the quality of the open data isn’t good enough to rely on – like Wikipedia ten years ago. But in a few years, information will only count if it’s open, and feedback will make the open data more accurate.

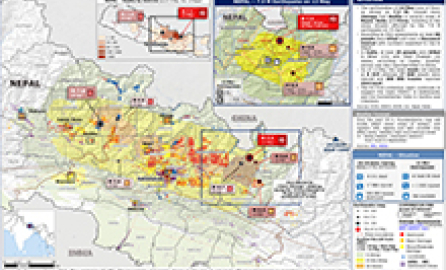

In this video, Simons explains how open data was used in the Nepal earthquake relief effort by a local civil society organisation, Open Nepal. Open Nepal developed a website to track the flows of humanitarian aid coming into the country and improve transparency of the international effort.

|

For more information on other mechanisms: The International Aid Transparency Initiative provides a mechanism for all actors (including donors and recipients, private sector, NGOs, etc.) to publish and share aid-related data. Their 2014 report identifies which countries are performing well in terms of publishing data, and which countries are not. This report summarises three pilot studies (Zambia, Ghana, Bangladesh) on aid transparency recently carried out by the United States government. Below you will find a selection of some of the many initiatives inspired (in part) to the open data sharing of humanitarian intervention:

|

|

For more information on Capacity4dev about the issues discussed in this article: Data Voices & Views:

Blogs:

Ebola In December 2014 capacity4dev focused on Ebola publishing a series of articles and videos. You can find out more, including links to all the content here. Improving Transparency and Effectiveness This article on Joint Programming explains another mechanism for improving aid transparency and effectiveness. |

This collaborative piece was drafted by Emma Brown with input from Rupert Simons and support from the capacity4dev.eu Coordination Team. Teaser image copyright of the European Union, 2015.

Log in with your EU Login account to post or comment on the platform.