Many children fall through the gaps in South Africa’s education system. Only half of learners in Grade 1 make it to Grade 12, and many fall short of exam requirements. The EU has been supporting South Africa’s Departments of Basic Education and Higher Education and Training since 2004 to move towards inclusive education for all, with specific measures to support learners with disabilities and from disadvantaged backgrounds. Capacity4dev hears about a programme providing books for every child; the rise of full-service schools; and improving vocational education.

“The support for inclusive education has been a really big intervention over many years,” said Marie Schoeman, Chief Education Specialist for Inclusive Education in South Africa’s National Department of Basic Education. “The EU funded the development of basic policies, systems and structures.”

These include:

- A Policy on Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support which ensures that every learner can attend and receive support in his or her local neighbourhood school

- The concept of universal design and access in the School Infrastructure Norms

- Guidelines for Full-Service/Inclusive Schools and for Special Schools as Resource Centres

- Guidelines for Curriculum Differentiation

- the establishment of School-based and District-based Support Teams that maximise support delivery at school level through multi-sectoral interventions

“Systemically these were very valuable interventions by the EU - it put us on the best footing to take inclusive education to scale,” said Schoeman.

The examples below show a glimpse of how the education system could evolve to support all learners, as well as the challenges still to be tackled. “In general there is cohesion between these projects,” said Schoeman. “They look at all learners who are experiencing barriers to learning, and improve their chances for through-put, which is a big concern in South Africa, where only a little more than half the learner population which starts in Grade R finishes school because of poverty, neglect and learning difficulties.”

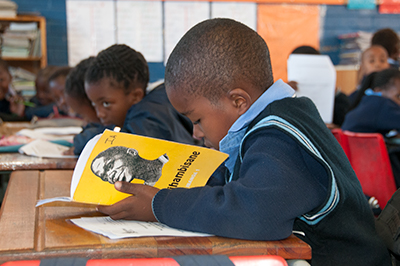

Books for every child

Literacy and numeracy rates are a cause for concern in many South African schools; in 2016 the government asked schools to condone a 20% maths pass mark for pupils in Grades 7-9. One of the fundamental issues over the years has been a lack of basic classroom resources such as workbooks – something the Department of Basic Education has helped to turn around since 2012 with EU support.

A workbook project, funded by the Department of Basic Education through the EU’s Primary Education Sector Policy Support Programme, aims to supply numeracy and literacy workbooks to every child from day one in Grade R to the end of compulsory education in Grade 9. Carried out by a joint venture of three firms – printing companies Lebone Litho and Paarl Media, and delivery firm UTI – it prints and delivers some 56 million workbooks each year to over 24,000 schools, the majority in rural areas.

In the process they created 3,600 permanent jobs across the production chain, from printing and packing to warehousing and distribution, and employ over 5,000 people at peak times.

“It’s an amazing success,” said Hubert Mathanzima Mweli, Director-General for Basic Education. “We started this project in 2012, and the improvement in numeracy and literacy from then till now is more than 20%. Learners in Grade 6 are now performing at Grade 6 level; unlike before, they used to perform at Grade 4 level.”

Printed on sustainable paper with toxin-free ink, the books are available in all eleven of South Africa’s official languages, plus braille and large print. All for the price of less than a croissant per book, according to Keith Michael, Chief Executive of Lebone Litho Printers.

In the following video Keith Michael and Mike Ehret outline the project. Skip to 0:05 for Hubert Mathanzima Mweli on the project’s impact; 1:00 for Keith and Mike on the logistical challenges and solutions; 2:16 for the IT system which keeps track of every book throughout the process; and 3:01 for the next steps in terms of scaling up.

“Where there’s a shortage of learning and teaching materials, this has filled an immense gap, making sure all children have a book in front of them,” said Schoeman. “In terms of inclusive education we were very happy they funded the production of work books in braille and large print, which go with tactile toolkits. That’s been a huge injection for our schools for the blind. They can be used right across Africa as they are excellent and revolutionary in the way children who are blind are being taught.”

With additional funding, Mweli would like to see the number of subjects increased beyond literacy, numeracy, English as an additional language and life skills, to cover all academic subjects as well as vocational education and training.

“It could work in different parts of Africa as well,” said Mike Ehret, Executive Director of Paarl Media. “The Minister of Education in Zimbabwe came and had a look and was excited about it, but clearly it’s a question of funding. We’ve also had visits from the EU Delegations to DRC, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Nigeria.”

Full-service schools

One school which has benefited from these books is Isiziba Primary School in Gauteng’s Ekhuruleni North District. It is one of around 900 full-service schools in South Africa – a relatively new breed of school adapted to welcome children with different educational needs.

“They are not supposed to be schools specializing in only taking kids with disabilities,” explained Schoeman. “It’s about best practice for inclusive education. The schools are capacitated to do differentiated teaching, they know about differentiated assessment, so they can do early interventions. It’s about creating a welcoming ethos and culture which would combat exclusion and promote inclusion, also of children with disabilities.”

Schools across the country are receiving support from the National Treasury to adapt their buildings for wheelchair access and improve teaching support and assessment, but this remains work in progress. Many of the schools – including the ‘flagship’ one Capacity4dev visited – still lack toilet facilities for wheelchair users, and need additional funding to ensure availability of specialist staff such as occupational and speech therapists and social workers. “We are currently finalising our funding norms to put all the full service schools on a stronger footing,” said Schoeman. “Teachers are receiving ongoing training on curriculum differentiation which is believed to improve their efficiency and effectiveness to be good teachers and should not be seen as an additional burden.”

At Isiziba Primary School, 108 of the 1,309 pupils have learning difficulties. All 35 teachers have been trained on the Guidelines for Full Service/Inclusive Schools and the Policy on Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support and received training on supporting learners who experience barriers to learning and development. A School Based Support Team (SBST) provides ongoing guidance to the teachers; and a learner support educator comes daily to provide remedial support to learners.

The school hopes to receive funding for more educational support staff, occupational therapists and social workers, which would make a big difference to the pupils’ development.

“There are many challenges,” said the Principal, Ms Nkosi. “Some of our pupils come from child-headed households; their parents work in other cities, so when we call them to meetings, they don’t come. It’s a less affluent area. For many pupils, the part of the day they look up to is getting breakfast and lunch from the school kitchen.”

Children travel as far as 30 km to attend the school, which is one of only two full service schools in the Tembisa area. “Some come by bus, some by taxi [minibus], and some walk,” said Nkosi.

The pupils gave Capacity4dev a tour of the school. Skip to 0:52 for Principal Nkosi on the school’s learners and languages; 1:19 for the food scheme and library; 1:50 for the Principal on the ongoing challenges, including overcrowding and lack of resources; 3:29 for Marie Schoeman from the Department of Basic Education on progress towards full service schools.

Developing the vocational pathway

Although teachers are being trained to adapt the academic curriculum for learners who experience barriers to learning, there is still a need for a more structured vocational curriculum. Many learners with an interest and aptitude for vocational education and training currently leave Grade 9 without a nationally-recognised exit-level qualification.

“The Department of Basic Education pushes schools to write the Annual National Assessment. But if you don’t follow the full curriculum, that means you’ll send your children into an exam they can’t pass,” said Dimitri Theron, Headmaster at Kempton Park Panorama School, one of 67 vocational schools in South Africa. “That is a serious challenge for us. Our learners do part academic, part vocational. We follow the mainstream adapted curriculum, and we also follow the departmental guidelines for vocational education and training. But it’s not standardized; so you cannot compare with other schools with learners like ours, as they will have adapted the curriculum differently,” said Theron.

This is something the Department of Basic Education is working to address. “The EU helped us develop a new vocational education policy, with an exit-level qualification, as well as 46 learning programmes,” said Schoeman. “26 of them are technical occupational programmes with an exit-level qualification at the end of basic education. On top of that, there are also programmes for learners with severe intellectual disability, and we also developed a policy framework and curriculum for learners with profound intellectual disability.”

Kempton Park Panorama School is considered a good example of a school providing vocational education while catering to learners with different needs. Based in Ekhuruleni North district, it takes in learners with moderate and severe intellectual disabilities, as well as learners with epilepsy and cerebral palsy. The school also offers remedial education and reading support to learners who would otherwise drop out of education – which means they have a second influx of learners from high schools in the second term of the year.

This makes staffing a challenge. The teacher to learner ratio should be 1: 15, as many classes are based in workshops where learners are handling specialist tools and equipment. However, most classes have 21 learners, and recruiting artisan staff is difficult. “It’s really hard to find people who are qualified, artisans who want to come into TVET,” said Theron. “It’s an area where we may need support in the future.”

An important part of the course is on the job training. The school cultivates links with bakeries, nursery schools and mechanical workshops which take learners for workplace skills development.

If learners find a job, “They will leave school,” said Theron. “Because work is a problem in South Africa. To find a job, even if you’re qualified, is difficult. If you stand last in the queue as you’re from a special school, you’d take the job rather than stay in school and do an endorsed matric [the university entrance requirement].”

In the following video, Capacity4dev visits workshops for motor mechanics, welding, hairdressing and cooking. Skip to 0:05 for Marie Schoeman on South Africa’s vocational education pathway; 0:33 for Dimitri Theron on the school and its learners; 1:49 for a motor mechanics workshop; 2:40 for welding; 3:30 for hairdressing; 4:12 for teacher training for primary education; 4:40 for cooking; and 5:20 for Theron on learners’ job prospects.

The vocational education programme is not only being introduced for the benefit of learners with disabilities, but aims to create differentiated curriculum pathways in senior primary and in secondary schools for learners who have an interest and aptitude in vocational education. It is considered a critical contribution of the Basic Education sector towards addressing the skills shortages of the country.

“The initiatives seen in this programme are examples of the wide scope of the journey towards inclusive education,” said Schoeman. “The South African Department of Basic Education is committed to providing opportunities for quality learning for all learners, irrespective of their abilities and socio-economic background. Schools are being capacitated to adopt inclusive policies, cultures and practices and the Department is ensuring availability of differentiated curriculum pathways and adequate resources to ensure that every learner will be able to develop his or her full potential.”

The most important lessons learnt since 2002 are that inclusive policies, systems and resources are critical to ensure radical and wide-scale transformation of the whole system, but that real change and successful implementation happen at community, school and classroom level.

“Teachers and school managers need to believe that every child has a right to belong and to be supported to develop optimally so as to be eventually included in society and the world of work as adults,” said Schoeman. “Specialist professionals should be made available in a consultative role to capacitate teachers through ongoing itinerant advisory services on how to support learners in the classroom through inclusive teaching methodologies.”

All this is at the heart of building an inclusive society, as laid out in the South African government’s 2009 National Development Plan: “The education system will play a greater role in building an inclusive society, providing equal opportunities and helping all South Africans to realise their full potential, in particular those previously disadvantaged by apartheid policies, namely black people, women and people with disabilities.”

|

The Teaching and Learning Development (TLD) Sector Reform Programme The TLD programme began in 2015 and aims to enhance the quantity and quality of teachers for all education sub-systems. It comprises Budget Support of €20 million, a Technical Assistance component of €1.7 million, and a CSO component of €4 million. The programme focuses developing a teacher education system that can deliver quality professional development programmes and opportunities for early childhood development educators, primary school teachers, special needs teachers, technical and vocational education and training lecturers, community education and training lecturers, and the professional development of university academics. |

Log in with your EU Login account to post or comment on the platform.