.linkfrench, .linkfrench:visited{ color: white; text-decoration: underline; }

This article is also available in French.

While the origins of COVID-19 are still unknown, most explanations point to an animal source. Although the transmission of diseases from animals to humans is not uncommon, this pandemic has intensified the debate on the widespread consumption of wild meat. The EU is co-funding a major international initiative to improve wildlife conservation and food security.

The hunting of wildlife for food (wild meat) has been in the spotlight since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The potential public health risk of consuming this kind of animal protein has divided the international community between those who would like to ban this practice and those who would like to regulate it better.

This is a complex debate; millions of people depend on wild meat for food and income, particularly in tropical and sub-tropical regions. Sustainable management of hunting for wild meat is needed to improve wildlife conservation and food security. To this end, the EU, together with the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (OACPS) and the French Facility for Global Environment (FFEM), launched – in 2018 – the Sustainable Wildlife Management (SWM) Programme in 13 countries1.

Best practices of the SWM Programme:

Sandra Ratiarison, SWM Coordinator for Central Africa and Madagascar (FAO), shares some of the innovative approaches used by the Programme:

- Flexible programming respecting community rights: The needs, rights and interests of indigenous people and local communities underpin all SWM Programme activities to ensure that the work is culturally sensitive and sustainable. The communities at the SWM Programme field sites are involved in defining the project objectives and activities that involve or may impact them. They are consulted about the practical implementation of the project, and agree on how to be kept informed through a Free, Prior and Informed Consent2 process.

- Adaptive management by integrating best practices: SWM uses a comprehensive monitoring, evaluation and learning system – based on the Theory of Change for the eight models of sustainable management of wild meat hunting being tested at the project sites – to assess and adapt project activities. This systematic approach allows the team to test hypotheses, generate lessons learned and apply best practices.

- Collaborative effort: The SWM Programme brings together partners with different views, areas of expertise and ways of operating. Its governance structure encourages debate and innovation. This environment encourages cross-sectoral and interdisciplinary approaches, such as the “One Health” approach to address the root causes of zoonotic diseases.

Solutions adapted to peoples’ needs: Congo and Gabon

The bottom-up approach adopted by the SWM Programme ensures the meaningful participation of the local communities at project sites. Germain Mavah, the SWM Coordinator in the Republic of the Congo (Wildlife Conservation Society), explains, "while searching for wildlife conservation and food security solutions, we need to work with the communities. It would be a waste of time and resources to promote fish farming in a village where the ecosystem and tradition is sheep breeding."

In Gabon, this dialogue with local communities has led to important adjustments in the SWM Programme focus. Sandra Ratiarison explains, "we initially proposed reducing community reliance on wild meat by encouraging the local production and trade of alternative animal protein, such as poultry or fish. We listened carefully to the community and discovered that most villages already had access to imported meat, but that they needed to continue benefitting from the income generated by wild meat to meet their basic needs."

Germain Mavah explains that the sustainability of wildlife resources for food in rural areas entails joining communities in wildlife management with those in urban areas. "One of the main solutions is to reduce wild meat consumption in regional towns and cities. Law enforcement alone has proved to be ineffective. In the SWM Programme, we believe that changing the wild meat consumption patterns by increasing the availability of sustainably produced meat and fish products, reducing wild meat availability, and encouraging food behaviour change can make a difference. In addition, developing new livelihood opportunities in peri-urban and rural areas by breeding and trading domestic animals can be profitable for both rural and urban people.”

Sharing experience and knowledge

Sharing information and innovative approaches is one of the main features of the SWM Programme. The SWM field teams are generating invaluable knowledge in many different disciplines. Topics range from wildlife hunting for food and wild meat value chains to consumption. They also cover different laws (statutory, customary) that regulate the management of natural resources, up to the changes needed in a wide range of aspects to achieve the dual goal of wildlife preservation and food security. This information will be used to expand and scale-up good practices.

In October 2020, in response to the public debate caused by the pandemic, the SMW Programme published the White paper: Build back better in a post-COVID-19 world – Reducing future wildlife-borne spillover of disease to humans.

Robert Nasi, Director General of the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), explains the idea behind the publication of this white paper and the associated policy brief, "the purpose was, amongst others, to balance the debate. It is not helpful to ban hunting and close public markets selling perishable goods without providing alternatives. The problem is not the wet markets but the supply chain."

The SWM Programme advocates preventative measures to reduce the risks of future disease outbreaks, create healthier and safer environments, and restore the balance between humans and nature. In Robert Nasi's words, "the proposals included in this policy brief are common sense."

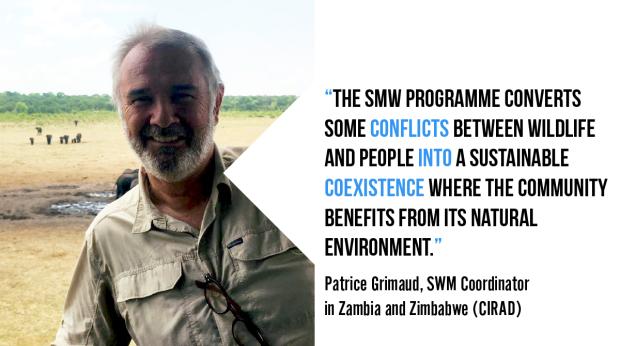

Human-nature balance in Zambia and Zimbabwe

Southern Africa is different. Patrice Grimaud from The French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD), who is the SWM Coordinator in Zambia and Zimbabwe, explains, "the problem in Central Africa is the human consumption of wild meat. The concern in Southern African countries is how to enable sustainable coexistence between wildlife and the local communities."

In countries like Zambia and Zimbabwe, hunting practices are highly regulated. The local population tends to consume animal protein from domesticated poultry or goats rather than wild meat. However, wild species are considered important for economic reasons (tourism mostly) but are often in conflict with the local communities that share their habitats. The disruption of markets caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has also led to an increase in poaching.

Conflicts arise when hyenas or other carnivores attack villages and when elephants trample agricultural crops. The SWM Programme works with the local administrations in charge of protected areas and national parks, private companies operating hunting reserves, and the local population, to find appropriate solutions.

Patrice Grimaud explains, "first, we conducted several field surveys to understand the environment and the challenges. We also organised information sessions with locals and stakeholders to understand their problems and needs." The Programme then helped the local population to find immediate solutions to limit conflict while improving livelihoods. This includes installation of mobile bomas, which are opaque plastic canvas structures, to protect livestock from attack by carnivores while increasing soil fertility, and installation of beehives next to the crops to both scare off elephants and enable villagers to obtain and market honey. Improved water management to avoid conflicts around water points is also encouraged. Longer-term sustainable solutions are also being explored through the creation of Community Conservancies3.

The need to find a sustainable balance between food security and the conservation of wild species is clear. The ongoing COVID-19 crisis has stressed the importance of preserving natural ecosystems, and reducing demand for wild meat where it is not a nutritional or cultural necessity, to reduce the risk of the next zoonotic disease spillover. The SWM Programme supported by the European Union plays an important role in tackling these complex issues, and developing solutions that can be adapted and replicated in many other countries and regions.

Click on the play button below to watch our video about the SWM Programme.

|

ABOUT SWM Programme |

Read the other episodes of the climate and environment series:

- Episode #1: Larger than Jaguars: Biodiversity protection in the LAC region

- Episode #3: Local heroes protecting the world's biodiversity hotspots

- Episode #4: Team Europe-Kenya Partnership: community-led wildlife conservation

Credit: Video © Capacity4dev | Photo © Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO)/Thomas Nicolon , 2019

[1] The SWM Programme is implemented by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), the Wildlife Conservation Society, the French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD), and the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) in Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Gabon, Guyana, Madagascar, Mali, Papua New Guinea, Senegal, Sudan, Republic of the Congo, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

[2] Free, Prior and Informed Consent (“FPIC”) is a specific right that pertains to indigenous peoples and is recognized in a series of international legal instruments. The right to FPIC is part of peoples’ collective right to self-determination, which not only allows them to grant or withdraw consent for a project at any stage, but also includes the right to determine what type of process of participation, consultation, and decision-making is appropriate for them. The SWM Programme extends this right to both Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in all its project activities. For more information on the SWM Programme approach, watch this short animation “Community rights and wildlife conservation”.

[3] Community Conservancies are legally-recognised, geographically-defined areas that have been formed by communities who have united to manage and benefit from wildlife and other natural resources.

Log in with your EU Login account to post or comment on the platform.