The idea of a health system that provides services and financial protection to all citizens has emerged shortly after the Second World War, through the development of the welfare state. In more recent years, the concept of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) emerged with the World Health Report in 2010 and was endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 2012. Since its inclusion in the Sustainable Development Goals 2015, however, UHC has gained unprecedented momentum, as countries around the world have begun defining their own paths towards achieving it by 2030.

Under Agenda 2030, the European Commission has committed itself to helping partner countries achieve UHC. In the first part of our series on Universal Health Coverage, Capacity4dev speaks to Dr Joseph Kutzin of WHO and Matthias Reinicke from DG DEVCO on the history of Universal Health Coverage and the common challenges to achieving it.

Lower-income groups in societies across the world face a cruel paradox when it comes to health – they are the most likely to fall ill, but usually are also the ones struggling the most to obtain and afford treatment.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), achieving universal health coverage (UHC) would ensure that all people and communities receive good quality services corresponding to their needs, and that the financial protection is ensured for all. Achieving UHC by 2030 is one of the targets of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

“UHC means that everyone is able to get good quality services, without the fear that paying for them will cause them severe financial hardship that would end up driving them into poverty,” said Dr Joseph Kutzin, Coordinator for Health Financing Policy at WHO. “As an aspirational statement, this is where we want to be. The real challenge lies in transforming this aspiration into something that can be adapted in any country or context.”

Dr Kutzin, who discussed health financing for UHC with EU Delegation staff in Brussels earlier this year, said that achieving UHC is primarily about providing more care with available resources to those who need it most, as well as finding additional funds needed to cater for the needs of each country’s population, in line with its specific disease profile.

“The distribution of ill health and the need for services is not even across society. It tends to be concentrated, and it’s a relatively small share of the population that will need substantial levels of health services,” he said. “The trick is to redistribute the resources to where the need is. Whenever there’s a degree of redistribution, you run into political challenges; it’s about how much solidarity is a society willing to support.”

Three dimensions of coverage

The pursuit of UHC emphasises covering all needs, including prevention, treatment and health education. According to WHO, strengthening primary health care (PHC) is the most sustainable path to take, because a focus on prevention, early detection of diseases, and health education will reduce the need for more expensive treatment services. But UHC goes well beyond PHC.

An independent commission of renowned economists and global health experts has shown that every dollar invested in health can generate between $9 and $20 of growth, depending on the intervention. But with life-expectancy increasing and health needs growing, reaching the goal of UHC will pose huge challenges, not only to developing countries, said Dr Kutzin.

In 2005, WHO member states made the commitment to set their own targets of developing health financing systems that are capable of ensuring – and, critically, sustaining – progress towards universal health coverage.

|

Dr Joseph Kutzin on the technical and political obstacles to achieving universal health coverage: |

Despite their different contexts, the governments of those countries all find themselves grappling with the same fundamental questions: Where and how to find the financial resources; how to protect people from the financial consequences of ill health; and how to make the most optimal use of resources.

Nevertheless, poorer countries will have to address the specific issues that may make their path towards UHC even steeper – particularly health systems, which will need to be strengthened in order to build the capacity to achieve UHC, and by so doing to all national health policy goals. To fund health systems for this purpose, improving tax collection will be essential, another major challenge in largely-informal economies. Increasing the priority for health in public resource allocation is another important step for many governments.

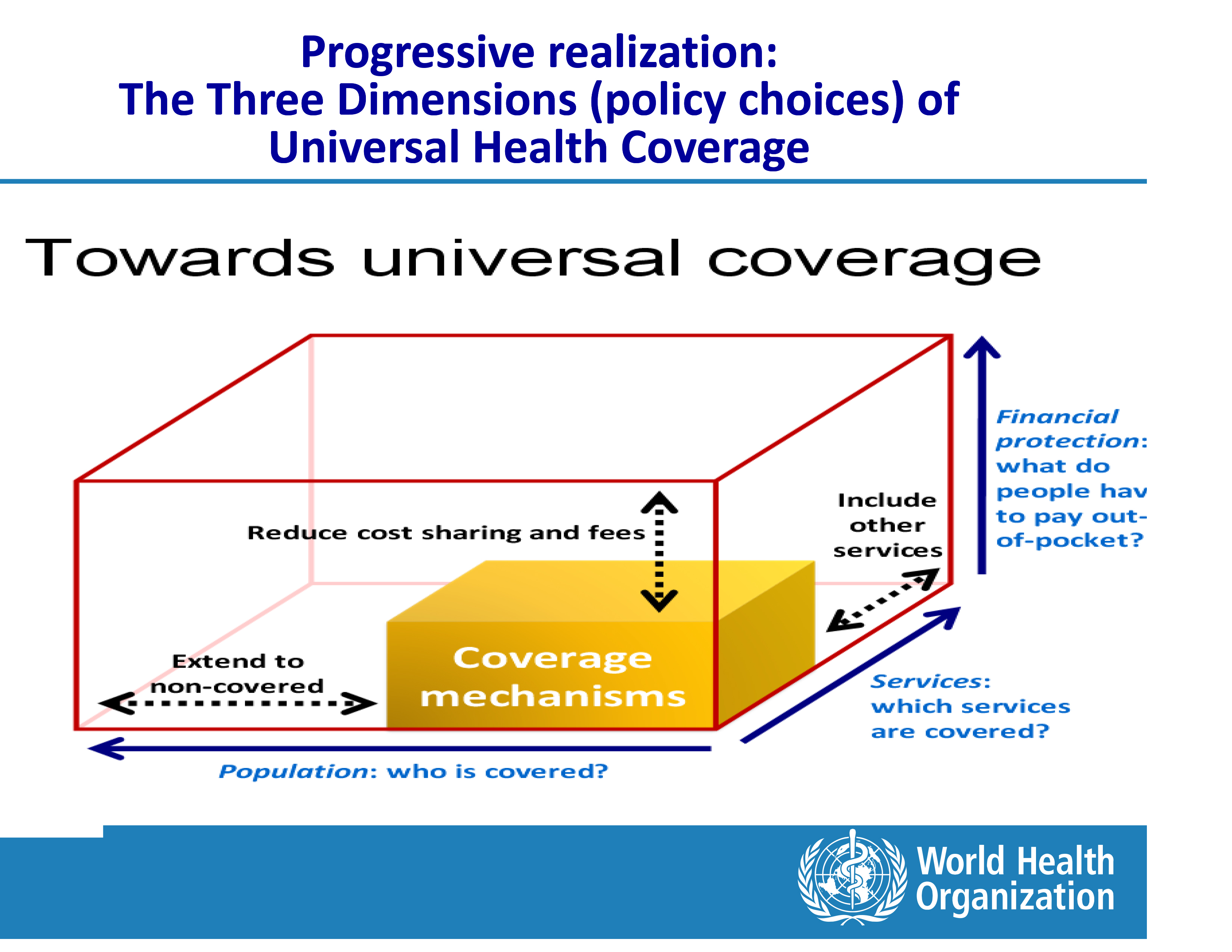

In its World Health Report from 2010, WHO provided a framework for how countries can analyse national health systems and their financing models to progress more quickly towards UHC, and to sustain those achievements. With that aim, the report made use of the so-called UHC Cube, a framework for thinking through policy choices with regard to extending health coverage benefits and for assessing who is actually getting what, and at what cost, in the national health system.

The UHC Cube |

This framework helps to answer the questions of how best to address equity in determining what the basic health service benefit package in a given country should entail, namely, which services the government should prioritise; which segments of the population will benefit from these services; and how the health system can most efficiently move the largest share of the health expenditure from out-of-pocket payments (i.e. cost falling on users) to prepayment systems where governments will assume a greater share of the costs.

“The cube essentially helps to make explicit that there are trade-offs between, for example, increasing service coverage as compared to improving financial protection (cost coverage) for some or all of the population, or making such policy choices that prioritise certain population groups over others, and so on,” Dr Kutzin said. “The aim is to make priorities and trade-offs explicit, and by doing so, to inform national policy debates.” Priority setting and consequent policy and strategy development need to be addressed when defining the national path towards UHC.

|

Dr Joseph Kutzin on the history of Universal Health Coverage and its connection to the Health Systems Strengthening: |

This framework, together with the broader health financing and system frameworks, Dr Kutzin added, can help with a systematic approach to tailoring health financing reforms to the characteristics of each national health system, taking into account the different political, economic, geographic, demographic and epidemiologic factors – a one-size-fits-all approach, he said, wouldn’t work with health.

“While tools, frameworks and guidance are available at a global level, fundamentally, these are meant to support, and not substitute for, our ability to think systematically and adapt to context,” Dr Kutzin said. “UHC risks becoming a slogan unless people really have a way to operationalise the concept. When the staff from EU Delegations returns to the countries where they work, we want them to go back with tougher questions, so that they can move past the labels and push for change more effectively.”

Fortunately, Dr Kutzin added, there is now a strong momentum behind UHC. “When we brought UHC to public attention with the World Health Report from 2010, we didn’t really invent the concept; universal health coverage dates back to at least WWII,” he said. “But the Report has reinvigorated the discussion, and UHC has gained political currency.”

Political and economic priorities

|

What is Health Systems Strengthening? Health Systems Strengthening (HSS) aims to improve the health system of a given country. HSS can entail any array of initiatives and strategies that sustainably improve one or more of the functions of the health system and that lead to better health through equitable improvements in access, coverage, quality, or efficiency of health services, thus resulting in improved population health. For more, read the WHO report "Systems Thinking for Health Systems Strengthening" |

But while the benefits of investing in health are undisputed, several countries are not allocating adequate resources to their Ministries of Health when overall resources are scarce, said Matthias Reinicke, Policy Officer at the European Commission’s Directorate General for International Cooperation and Development (DEVCO).

“It is a question of money, that’s very clear. But it is also a question of how much priority a country gives to achieving UHC by its own means,” Reinicke said, adding that UHC is an attainable goal for all countries, irrespective of their per-capita health expenditure.

“Take the United States, where arguably the per-capita-expenditure on health is one of the highest in the world, and yet a good share of population is not sufficiently covered,” he said. “On the other hand, in some much poorer countries, if you look at specific diseases or at targeted health services like maternal health, around 80% of the population in need are covered, up to 90% in some countries.”

|

Matthias Reinicke on the priorities given to UHC in various countries and on the importance of domestic resource mobilisation: |

The ultimate objective is for countries to achieve domestic resource mobilisation (as recognised in the Addis Ababa Agenda for Action), and not rely on external funding, Reinicke added.

Another lesson, Reinicke said, is that countries must commit to achieving UHC. “Because we see that countries that find themselves in similar circumstances – but who have set ambitious targets – are on their way to achieving the results. So the short answer is, yes, UHC can be achieved by everyone, but it must become the countries’ first priority.”

Disclaimer: This collaborative piece was written by Capacity4dev’s Coordination Team, with input from the B4 Unit at DG DEVCO, the World Health Organization and the Health Advisory Service.

Log in with your EU Login account to post or comment on the platform.