If you work for an EU Delegation, join the EC Education Focal Persons' discussion on public and private provisions of education here.

Various forms of private education have emerged in recent years in developing countries.

Is this an important contribution to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals or a worrying trend that will disenfranchise the poor?

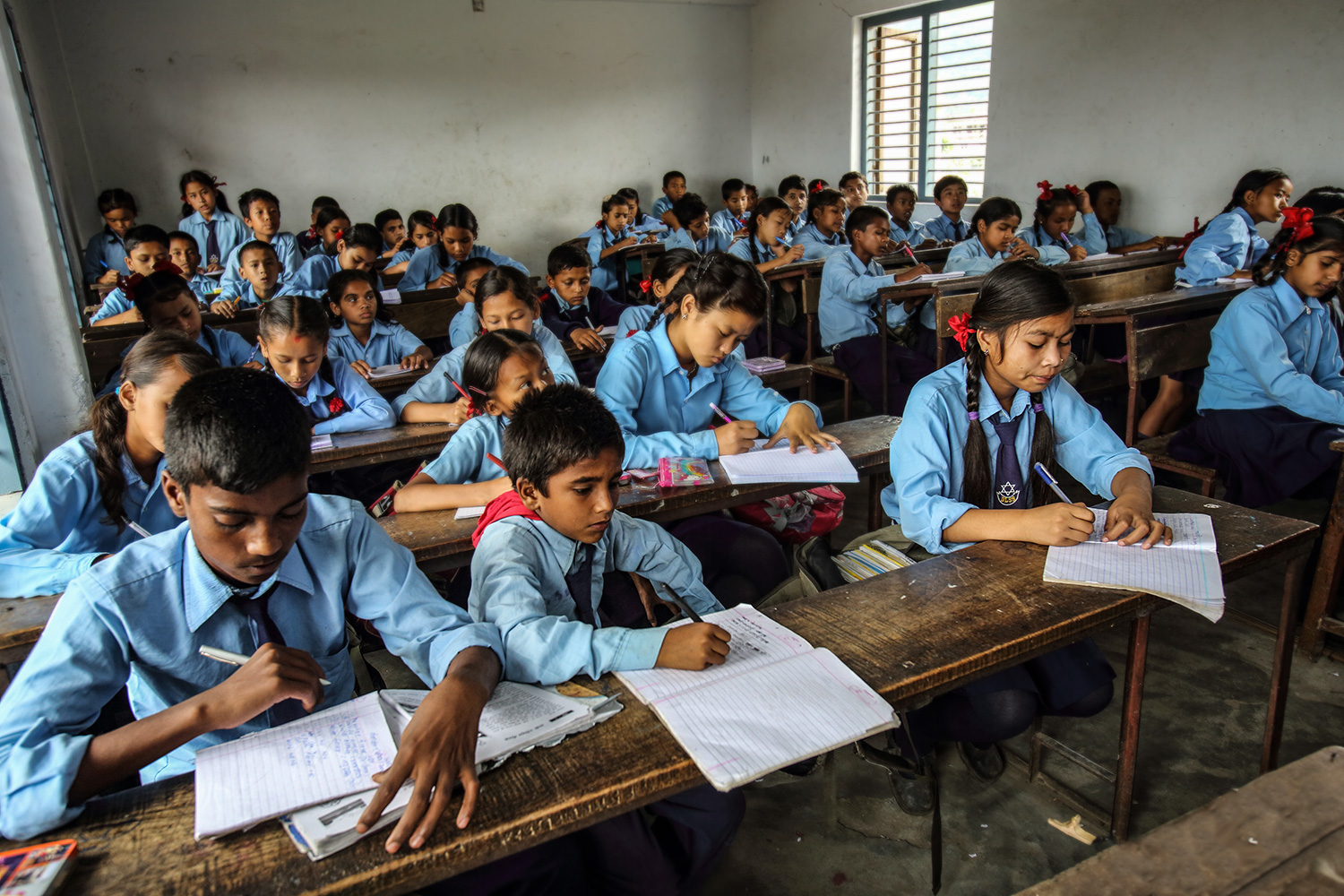

With 264 million children lacking access to quality education, should the private sector step in to fill the gap? Photo © Jim Holmes/AusAID

With at least 264 million children out of school, should private education providers fill the breach left by governments?

In some countries and regions, private schools already outnumber the public sector.

In Kathmandu, Nepal's capital, for example, 78% of schools are private, and 70% of children attend private schools.

The issue of whether private education in developing countries complements and supports the right to education or makes education only accessible to those who can afford to pay has sparked heated debate in development circles.

Capacity4dev asked three education practitioners about their views:

- Pramod Bhatta, a researcher who co-authored a study on the patterns of privatisation in his native Nepal;

- Peter Colenso, from the Innovative Development Progress (IDP) Foundation Inc., which supports low-cost private schools;

- David Archer, from ActionAid International, member of the Global Campaign for Education, a network advocating for free and public universal education.

▼ The impact of private education in Nepal

In Kathmandu, Nepal, 78% of schools are private, and 70% of children attend private schools. Photo © Simona Cerrato/Flickr

In Nepal, non-state schools make up about 19% of the education provision. For Pramod Bhatta, a lecturer of sociology at the Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu, the private sector’s rising influence is a cause for concern.

Why are more children in Southeast Asia attending private schools?

“In some areas of the country that have seen rapid population growth, there have been no new state schools established in the last ten years,” he said. “This means that whatever new population is migrating there, they are going to attend private schools.”

“In Nepal, one’s socio-economic status is closely associated with which type of school one goes to.”

Bhatta is sceptical of the argument that these private schools cater to families from all socio-economic groups.

His research found that while more than 65% of children from the richest 20% of the population go to private schools, only 6% from the poorest quintile do so as well.

“In Nepal, one’s socio-economic status is closely associated with which type of school one goes to,” he said.

Bhatta’s research also shows that private schools consistently outperform their public counterparts in annual board examinations, such as the school-leaving certificate examinations.

Nepal has achieved near-universal access to education, but quality of state education has not stayed on par, said David Archer. Photo © World Bank

Combined with the fact that private schools cater to children from more affluent backgrounds, the risk is that students from public and private schools will never meet. This, Bhatta said, is “an even bigger concern for greater social harmonisation and integration of the country”.

What is the socio-economic impact of the growth in private education?

In terms of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, the Nepalese government has increased public access, with an impressive 97% enrolment in primary education.

Nevertheless, this has resulted in the decline of quality of state education, mainly due to the lack of adequate public investment.

As a result, Bhatta added, the public system has become overloaded, and standards have dropped, so parents who can afford it move their children into the private system.

There have been attempts to raise education levels through, for example, the Education Amendment Act in 2016 and Education Regulations, which cover both the state and private sector. These regulations stipulate the curriculum, text books, teachers’ pay and conditions, and general norms and standards.

What can happen if the private education sector outgrows the public one?

However, Bhatta said, such regulations are difficult to enforce on the private sector.

“When the private sector becomes bigger in size, it also risks becoming too powerful.”

“When the private sector becomes bigger in size, it also risks becoming too powerful,” he said.

“We have seen that in the case of Nepal, where private schools have become increasingly organised, interest groups establish and push for certain arrangements, like the stripping of fee ceilings.”

Bhatta is wary of the increasing role of the private sector, but he realises it is there to stay. He said that while regulatory oversight is crucial, the government should not attempt to remove private schools altogether.

“These regulatory mechanisms need to act as filter between schools that are doing well and schools that are doing completely unrelated things in the name of education,” he said.

▼ Low-fee private schools and public-private partnerships

The role of the private sector in providing access to education has increased significantly since the early 2000s. Photo © UN Photo/Tobin Jones

Through its IDP Rising Schools Program, the IDP Foundation, a private non-profit foundation based in Chicago, says it has supported almost 600 low-fee private schools that serve low-income communities in Ghana – benefitting 150,000 pupils.

How to ensure quality and equity in private schools?

Peter Colenso, a consultant with the Foundation, says the aim isn’t to compete with public schools.

“We don't see [private schools] as a substitute for government schools,” he said. “We see public sector education as being ultimately the most important form of financing and provision.”

“We don't see private schools as a substitute for government schools.”

IDP provides small fee-paying schools with access to capital from the banking system and helps them improve the quality of their education by giving them access to educational goods and services. It also works with the non-profit Sesame Workshop to develop educational materials.

Colenso mentioned other approaches organisations have taken to improve the performance of public schools.

In India, for example, the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation partnered with Varthana, a financial services company, which gave schools loans and then incentivised them to improve quality by reducing the interest rate based on their achieving measurable improvements.

Why the criticism towards the private provision of education?

Without government subsidy, private education may not be viable for the poorest quintile of the population, said Peter Colenso. Photo © UN Photo/JC McIlwaine

Colenso insisted that IDP’s role is not to encourage parents in the bottom quintile to go for the private school option, especially if they can’t afford it.

He acknowledged that without government subsidy private education may not be viable for the poorest quintile of the population.

One way of addressing the equity issue, he said, are private-public partnerships.

“The low-fee private school market can serve households who are willing and able to pay, but if our aim is to reach the bottom quintile (the poorest students), those households would probably be unable to pay without seriously compromising their welfare. In that case, it’s probably best to think about public subsidy,” Colenso said.

“The low-fee private school market can serve households who are willing and able to pay.”

He pointed to the example of the Punjab Education Foundation, in Pakistan, which receives a government subsidy to distribute vouchers for 2.5 million children to attend private primary and secondary schools free of charge. On average, Colenso said, PEF schools outperform comparable government schools in regular learning assessments.

How should development actors engage with the private sector?

Colenso acknowledged that in most places, the state remains, and indeed should remain, the dominant funder and provider of primary and secondary education.

In his view, however, private schools are not inherently contrary to the right to free education, enshrined in international human rights law.

Instead, Colenso sees public and private education sectors as complementary.

To him, markets by their nature are not equitable distributors of wealth, and so effective government regulation is critical. He said private markets can be harnessed to improve education for all.

“My hope is that development actors are able to take on a mindset that looks at national education systems as comprising of both public and private financing and provision,” he added.

▼ Push for regulation and domestic spending

More and more parents around the world are moving their children to private schools. Photo © Albert González Farran/UNAMID

School fees are widely recognised as one of the strongest barriers to achieving universal primary education and gender equality.

According to David Archer, whose organisation ActionAid International is part of the Global Campaign for Education, the abolition of those fees has been the primary factor behind the rise in global enrolment rates in primary education since 2000.

Why are more children in developing countries attending private schools?

This rapid expansion, however, has had an unintended consequence: as governments have struggled to prioritise finding additional funding for education, public schools in many countries have become overcrowded and the quality of teaching has declined.

As a result, more and more parents are moving their children to private schools.

The domination by international chains of schools is a contentious aspect of private education, said David Archer. Photo © GPE/Adrien Boucher

While Archer sees this as a worrying trend, he does acknowledge some positive aspects of non-state schools.

“I think there are a lot of very interesting innovations that non-state actors have been implementing,” he said.

“For example, NGOs working with children with disabilities or in impoverished communities that look at creating inclusive education. Unfortunately, this is often unsustainable, so the priority must be to draw on this learning to help reform public education systems.”

Turning to the commercially-run private schools, Archer negates the claim that private schools achieve better results, once you control for socio-economic status.

Family background, he said, is a much stronger determinant of positive exam results than teaching – students with good results in private schools would have done just as well in state schools.

What are the risks associated with private education?

A contentious aspect of private education is the domination by international chains of schools, and Archer said these need to be strongly regulated.

This growing trend has prompted the Global Initiative for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights to draw up a set of guiding principles on the role of non-state actors in education, to be finalised this spring in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire.

The principles, Archer said, will “offer governments guidance on how to regulate private providers effectively and suggest that where schools fail, the government must be prepared to take them over”.

A corollary of this is the need to increase domestic education spending, said Archer. At present many developing countries rely on outside donors – such as the EU – to strengthen education provision.

Archer stressed that governments cannot rely on this but should ramp up their domestic education spending towards 20% of the national budget. They should also increase their tax revenue in progressive ways, allocate with sensitivity to equity and scrutinise spending to make sure it leads to concrete results.

✎

This article is part of a thematic series on education and development. Access more articles and videos here.

This article was written by Daphne Davis, journalist for Capacity4dev, with reporting and editing by Bartosz Brzezinski. Photo © Charles Chan/Flickr