Women and girls are at the heart of rural communities worldwide. Their contribution to ending poverty and ensuring food security is fundamental. They also play a critical role in natural resource management and can influence how their communities hunt and fish, improve sanitation, protect habitats and comply with conservation laws.

Women make up 43 per cent of the global agricultural labour force, according to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO). Nevertheless, their role is often invisible due to discriminatory social norms and lack of access to land, forest rights and decision-making processes.

Since 2018, the EU co-funded Sustainable Wildlife Management (SWM) Programme has been working with rural communities to improve wildlife conservation and food security in 15 countries in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific1.

This article gathers together the voices of gender experts working for the SWM Programme in Papua New Guinea, Congo and Guyana. The aim is to present their diverse experiences on effectively mainstreaming gender in project activities, and to inspire other development practitioners with the good practices they have been implementing.

Lessons learnt on ensuring gender equality and empowerment of women in SWM Programme activities:

Mauro Bottaro, social safeguards focal point for the SWM Programme, emphasises four important approaches to reducing the gender gap between women and men and improving sustainable wildlife management and food security:

- Set up a comprehensive gender-mainstreaming approach along the project cycle, including dedicated staff and the collection of sex-disaggregated data.

- Reinforce staff capacity through technical training and awareness-raising initiatives.

- Empower women and men from local and indigenous communities through all SWM Programme activities.

- Develop and use gender-sensitive indicators and document good practices.

1.Setting up a comprehensive gender-mainstreaming approach along the project cycle

The promotion of gender equality and women’s empowerment is embedded in the SWM Programme’s community rights-based approach. Mauro Bottaro explains that the initial challenge “was to build a common vision of the gender approach that was relevant and applicable in sites and countries with incredibly diverse social and cultural norms2.”

One of the first steps was to identify gender focal points in each site in order to “have staff specifically dedicated to gender activities.” The priority was to understand the different needs, roles and rights of women, men and youth within the community.

The SWM Programme recruited gender specialists to work with local communities and conduct gender analyses, community and household assessments and collect sex-disaggregated data. Michelle Kenyon, the SWM gender expert in Guyana, points out, “we have a bottom-up approach in which local communities and organisations implement 99% of our activities.” But most importantly, it involves rural women. Barbara Avelino, SWM gender expert in Congo, explains, “When we received candidatures for data collectors, we noticed that women had proportionally fewer school diplomas. By detailing the requested education level when recruiting data collectors, we were unconsciously excluding women. So we decided to adapt the recruitment process and subsequently organise comprehensive training, which was recognised with a certificate, before they began performing their data collection work. Like this, they could also present the certificate to future employers.”

2. Reinforcing staff capacity through technical training and awareness-raising initiatives

The SWM Programme also trains the technical and field staff responsible for implementing the activities by increasing their knowledge and technical skills, and addressing stereotypes and discriminatory attitudes and practices.

“We work in conservation, and whilst we understand the importance of gender, it can be challenging to connect the two,” says Barbara Avelino. To better understand how gender issues and effective conservation are intertwined, and to therefore improve programme implementation, the SWM Programme organises training and capacity development initiatives.

In Guyana, Michelle Kenyon reinforces the idea of comradeship between local implementing partners, “we build upon existing initiatives; our biggest contribution is creating a space where our local partners are able to better understand how each partner is contributing to sustainable wildlife management in the Rupununi3 landscape and creating partnerships which will be sustained after the SWM programme comes to an end,” she says.

3. Empower women and men from local and indigenous communities through all SWM Programme activities

Gender-based marginalization is a global cross-cultural phenomenon. It is therefore challenging to achieve community ownership and inclusive decision-making through active participation of all community leaders. The SWM Programme strives to support community-based natural resource management, providing “safe spaces in which everyone can express themselves,” says Barbara Avelino. In Congo, voluntary non-mixed focus groups are formed with community members based on their gender, ethnicity and age, allowing participants to share ideas without feeling pressured.

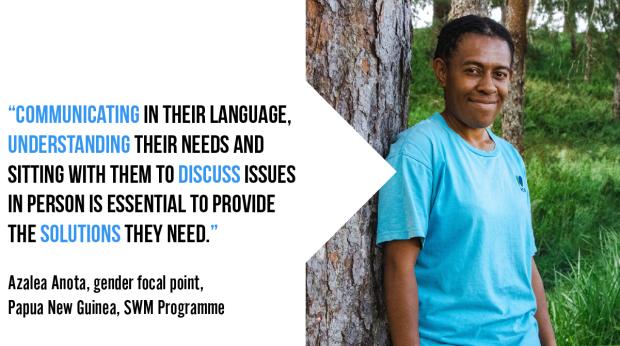

In Papua New Guinea, women do not share their opinions in public, for this reason, the solution is to separate community groups by sex. Azalea Anota, the SWM gender focal point at the project site in this country, explains “I am the only woman in my team, and it is often challenging to stand up and address the community in front of male leaders. It is not always accepted, but building community awareness is helping to show that women are not speaking up to intimidate but to help”. One of her greatest achievements was to guarantee that women could share their concerns and access resources during the establishment of community-led conservation deeds4.

Another way to address gender stereotypes is to give visibility to the crucial role of women and their contribution to poverty reduction. “In Northern Congo, women are overrepresented as family caregivers in charge of household nutrition and education. Nevertheless, they are also leaders in food sales, especially bushmeat”, says Barbara Avelino. The SWM Programme is actively implementing projects to support women’s empowerment through sustainable livelihoods and livestock production to replace the consumption and trade of bushmeat. For example, in Congo, small-scale sustainable companies are being planned with people involved in the wild meat trade, primarily women. In Guyana, the SWM Programme is running a competition with ten communities to distribute chickens to female heads of households allowing them to diversify their income. Poultry is seen as one of the most viable and preferred alternatives to wild meat consumption, and is being actively supported through SWM Programme training. In Papua New Guinea, “women prefer chicken because they are concerned about their children’s nutrition” says Azalea Anota. However, she adds “our objective is to support families without increasing their burden.”

4. Developing and using gender-sensitive indicators and documenting good practices

The SWM Programme has also developed, and is using, gender-sensitive indicators to track progress and ensure that activities will benefit women and men equally. This monitoring system is also being used to help adapt management plans as needed. Mauro Bottaro highlights, “we document and disseminate good practices so that viable solutions can be adapted and replicated in similar initiatives in the conservation sector.’’

Conclusions

Barbara Avelino confesses that one of the biggest challenges when working to reduce gender inequalities is that “we might feel overwhelmed by the number of things we need to address... our main focus should remain to ‘do no harm’ and not exacerbate these inequalities while implementing our programmes.”

The gender experts consulted for this article agree that rural women often face many similar challenges. They also agree that large conservation and food security initiatives such as the SWM Programme can play an important role in promoting gender equality.

Mauro Bottaro concludes that “really understanding the cultural context, social norms and how they shape gender relations is the prerequisite to engaging with local communities and authorities. Effective project interventions should be built on this understanding if they are to truly empower both women and men and be sustainable in the long-term.”

Click on the play button below to watch our video about the SWM Programme.

Have you been involved in relevant interventions for the promotion of gender equality and sustainable wildlife management?

What was your approach?

Did you meet any challenges, and how did you address them?

Leave your comment below!

|

More about the SWM Programme

Counting for better conservation - Building capacity in local communities in Senegal (Astou) |

Credit: Video © Capacity4dev | Photo © Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO)/Thomas Nicolon, 2019

1 The SWM programme is implemented in Botswana, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Gabon, Guyana, Madagascar, Mali, Namibia, Papua New Guinea, Senegal, Sudan, Republic of the Congo, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

2 To generate this common vision, a gender mainstreaming group was organised in which two representatives from FAO headquarters and one representative from the Wildlife Conservation Society, the French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD), and the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) agreed on the principles and produced tools for internal use including guidelines, templates, forms, gender analysis and indicators specific for each social safeguard in the monitoring system of the programme.

3 The Rupununi is a region in the south-west of Guyana, bordering the Brazilian Amazon.

4 A voluntary legal agreement between the clans, which provides strong legal protection of community natural areas for 3 to 7 years

Log in with your EU Login account to post or comment on the platform.