Biased, me? Never!

Well, here is the thing, we all are.…

The question is, how do we confront our gut instinct when faced with cultural difference.

In the previous article, we looked at how our cultural background can influence our behaviour in the workplace.

A lot of the time we are not even aware this is happening.

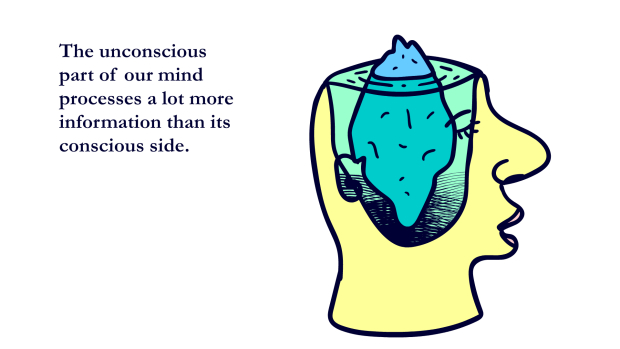

The unconscious part of our mind processes a lot more information than its conscious side, relying on shortcuts based on our background, personal experiences and cultural upbringing. It’s like an autopilot.

On the plus side, our “autopilot” enables us to make rapid decisions about everything around us. The problem arises when those judgements are biased – especially when we’re confronted with cultural difference.

Let’s take a look at one of the examples from the first article in our series:

You have recently moved and started a new position in an EU delegation; you have been there for a couple of weeks. Today, you have a review meeting with your team, and you would like to brainstorm about an issue. You are used to collaborative discussions, but you notice that only a few team members are actively participating – others remain silent.

Close your eyes and imagine what the quieter colleagues look like. Are they men or women? Expats or local staff? What do you think?

Chances are your unconscious biases are influencing the mental picture. They are the first images to pop into your head.

Unconscious biases come in many shapes and forms, helping us make snap judgements of the people we meet, categorising them according to gender, social characteristics, and other traits. But because they often lead to stereotyping – or worse, prejudice – it’s best if we learn to become aware of them and challenge them.

Towards an intercultural approach

The key here is to take a step back and acknowledge our implicit biases. These biases hold a grip on our perception of cultural difference and how we approach and interact with others.

American sociologist Milton Bennet is credited with creating a framework that describes the different stages of how we experience cultural differences, called the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity.

Denial

The closer we are to the ethnocentric side of the framework, the more likely are we to assume that our culture is the only valid one – the one closest to “reality”. We refuse to admit that people can live differently from us – due to their sexual orientation or ethnic background, for instance – and as such when faced with their difference, we deny them their humanity altogether.

Defence & minimisation

In lesser extremes, we might acknowledge that differences exist, yet we try to fight them (defence) – often with the use of stereotypes – or assume that because we’re all human, we share the same universal experience (minimisation).

We all tend to experience some level of discomfort when faced with new, unfamiliar scenarios. Moving to a foreign country or joining a new team – these situations can make us feel culturally uprooted and uncomfortable. This is perfectly normal.

Does this resonate with you at all? Remember that the ex-InCA group is a safe space, so feel free to share your experiences in the comments section below.

A way to deal with the feeling of uprootedness and to foster connectedness is to develop a sense of intercultural competence. At the other side of Bennet’s continuum is ethnorelativism – where we experience our culture in the context of others.

Acceptance & adaptation

When we build up intercultural competence, we learn to be curious, observe and appreciate other cultures. Instead of perceiving differences as a threat to our identity, we learn to accept them as part of the whole (acceptance) and adapt our communication and behaviour more easily to fit the context (adaptation).

Becoming aware of our gut feelings, snap thoughts, and reactions, and realising that we might need to reassess them when they stray too far into stereotyping, is just one of the skills you’ll develop through the ex-InCA programme.

Ultimately, an intercultural approach can enable us to more easily and efficiently interact with peers from different backgrounds. And though we might never all reach Bennet’s final stage of integration, where we are capable of internalising several frames of references and fully assess our experiences from the perspective of others, aiming to do so can help us become better development professionals.

So, as you have seen, we are all biased to some degree – a lot of the time, we are simply not aware of it. The good news is there are ways to challenge ourselves.

What do you think – where do you fall on the Bennet continuum and how do you deal with your unconscious biases? Add your comments below.

More from the ex-InCA series: