Ch-ch-ch-ch-changes: How to adapt to new contexts and why it matters

Settling in – and fitting in – can be one of the biggest challenges when moving abroad, starting a job, or even joining a project.

That’s because successful adaptation to a new environment more often than not requires disturbing our frame of reference – the way we perceive ourselves, the world and those around us (for more on this see Everywhere, all the time: What is culture in the intercultural approach?)

To be able to face such changes, we need to develop ‘real resilience’ – the capacity to absorb the disturbance to our frame of reference. This entails creating a new identity that nevertheless remains integral to who we are – containing enough of the old and familiar but allowing us to integrate into the new context.

Adapted by ex-InCA from the works of biologist Brian Walker, the process of building this resilience is somewhat akin to writing a new chapter in your life…

Ability to face changes

Imagine you are moving to a new country for work. Driven by curiosity, in the early creative phase, you’re excited to be taking on a new challenge, so you begin reading up on the local history and customs, eager to try out the new food and mingle with the locals.

But then you get there and reality kicks in. You realise this may be more than you’ve bargained for – you might find yourself not fitting in – or not willing to. Thoughts race through your mind: “This is more than what I’m used to. I like the way it is back home. I don’t really want to change.”

As the creation phase grows and settles, the excitement fades, and we lose the creative energy. As we focus on “getting the job done”, there is now a lot more control and rigidity in the structure. Instead of adapting to the new context and disturbances, we stick to familiar procedures and processes.

This stage – known as the conservation phase – isn’t necessarily always a bad thing, but when we get stuck in this mode and refuse to evolve according to circumstance, it can become an issue – change does need to happen after all.

Hanging on to what seems safe can stem from our fear of letting go or from our natural tendency to cling onto what is familiar (our cultural values for instance), even when it is uncomfortable. And this resistance is not just an individual’s struggle – organisations suffer from it as well, resisting change by relying on, for example, increased bureaucracy.

A way to get through this is to leap into the creative edge of chaos, experiencing the disturbance and diving deeper to discover the core values. In the most basic form, it might entail embracing elements of the local dress code – if only to show that you respect the local people. This phase usually carries some loss.

If we resist and dismiss this, we risk collapsing at the expense of whatever energy we have left.

If we succeed, we start to see the emergence of change as we move to the final phase of transformation. You regain energy and focus. Valuing creativity and change, you begin to reorganise yourself and experience something new – adapting enough for it to be appropriate to the new context.

Questions you might be asking yourself throughout include: “What really needs to shift?” “What keeps me/us stuck?” “What might we need to let go of whilst in the creative edge of chaos phase? How do we want to transform?” Let us know in the comments if you’ve ever undergone a similar process of adaptation.

From the intercultural point of view, it is essential to always reflect on the cultural elements that may foster or hinder resilience – analysing from everyone’s perspective why and how we need to adapt our approach.

How? With an ethical framework

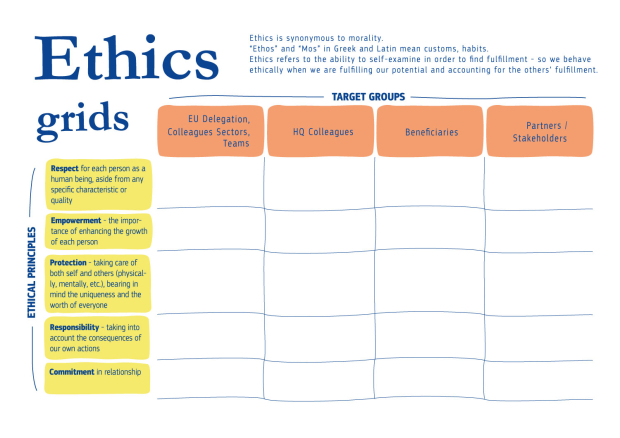

When working on projects and programmes, for example, using an ethical framework enables us to see how protective and respective we are of the different groups involved – our colleagues at the EU Delegation or in HQ, the partners and government stakeholders, as well as the beneficiaries.

It’s a powerful way to identify where the cultural issues might lie and to ensure an ethical cultural approach. Could a cultural misunderstanding be behind the lack of enthusiasm from the beneficiaries for your project? Are you imposing your own cultural viewpoint on the partners in the local government – or even colleagues at your own Delegation?

The ethics grid helps to bring about awareness of self and others into our work, helping us pinpoint and explain any resistance while avoiding intercultural blind spots.

When faced with projects involving a lot of people with different cultural values and approaches, this is a useful exercise no matter what topics you’re working on – whether it’s nutrition, health, gender or human rights.

Consider joining the ex-InCA workshop to learn more about our ethical framework and how to use it in practice. As always, share your reflections in the comments below. And for now, that’s all from our series of articles on the intercultural approach – we hope you enjoyed them!

More from the ex-InCA series:

- Everywhere, all the time: What is culture in the intercultural approach?

- One-minute video to summarize: What is culture in the intercultural approach?

- My culture, your culture: How our values influence the way we work

- One-minute video to summarize: My culture...your culture are ok

- Biased, me? Never!

- One-minute video to summarize: Unconscious bias