1.3.1 Trends in employment

1.3. Trends and characteristics of the informal economy

1.3.1. Trends in employment

While the criteria for the measurement of informal sector and informal employment were introduced in the national surveys, policy-makers sometimes showed some reluctance to use these terms. For example, as previously mentioned, Kenya preferred referring to ‘Jua Kali’ and Tunisia designed policies addressing crafts and small businesses. However, year after year, indicators on informality have been compiled, the size and significance of which depend on the countries social structures, national and local economic policies, and governments’ willingness of enforcing their own fiscal or labour legislation.

Today estimates of informal employment and informal sector employment exist in many countries, sometimes for long periods. Yet systematic and comprehensive comparisons worldwide remain difficult for at least two reasons. Firstly, the harmonisation of concepts at the international level is far from being reached. Secondly – and especially – the two concepts of informal sector and informal employment are neither mutually exclusive(and as such not additive), nor is the latter inclusive of the former, i.e. informal employment does not include the informal sector in totality. This is why statistics of informal employment and informal sector employment are generally presented separately. This paper deliberately opts for a definition of employment in the informal economy as comprising employment in the informal sector and informal employment outside the informal sector (i.e. the unprotected workers in the formal sector and the domestic workers in the households, not to mention the persons working in the production of goods for own final use by the households).

Despite such difficulties, macro-economic pictures of the informal economy, as a share of labour force or production (GDP), have long been estimated by economists and statisticians and used for policy purposes. Many of them have existed at national level since the late 1970s-early 1980s, but it was in 1990 that Charmes presented a first tentative international comparison at the global level in the OECD “Informal sector revisited” (1990). This work was updated in 2002 for the ILO-WIEGO “Women and men in the informal economy” prepared for consideration by the 90th International Labour Conference, and in 2008 for the OECD publication “Is Informal normal?” The tables presented in this paper have been prepared for the updating 2012 of the ILO-WIEGO publication and updated since then.

Table 1 hereafter attempts to assess the trends of employment in the informal economy by 5-year periods over the past four decades. The interpretation of this table requires three preliminary remarks.

Firstly, the indicator is based on non-agricultural employment while the definitions of the informal sector, informal employment and the informal economy are inclusive of agricultural activities. There are two reasons why an indicator based on non-agricultural employment has been preferred. The first is thatin countries where agriculture occupies the bulk of the labour force (most sub-Saharan, Southern and Eastern Asian countries for example), the share of employment in the informal economy including agriculture is above 90% and as such, changes over time may not be visible because of the volume of the labour force. The second is because the importance of change may remain hidden by the dramatic flows of rural-urban migrations. An indicator based on non-agricultural employment makes these changes more visible and its greater variability is a better tracer of change.

Secondly, the table is based on estimates prepared along various procedures, which have changed over time depending on the availability of sources and data. Therefore it is far from being homogeneous in definitions and methods of compilation. Sources for this table have been given in details in Charmes (2009). From the mid-1970s and until the end of the 1980s-early 1990s, the figures for the first three 5-year periods (in Northern Africa, sub-Saharan Africa and Asia) mainly result from an application of the residual method, which consists incomparing total employment (in population censuses or labour force surveys) and registered employment (in economic or establishment censuses or administrative records); censuses of establishments – where they exist – allow identifying the informal sector on the one hand and informal employment outside the informal sector on the other hand. From the beginning of the 1990s, the results mainly come from the first mixed surveys and focus on the informal sector, while in the 2000s the labour force surveys become the main source of data and provide data on informal employment and employment in the informal economy at large.

Thirdly, another limitation comes from the fact that it is not exactly the same set of countries for which estimates are available from one period to another. Consequently the average can become non significant unless there is a presence of at least a few countries over all of the periods.

Despite these limitations several observations and conclusions can be drawn.

Until the end of the 2000s, the informal economy wason the rise in all regions: with53% of non-agricultural employment in Northern Africa, 72.3% in sub-Saharan Africa, 57.7% in Latin America69.7% in Southern and South-Eastern Asia, and 25.1% in transition countries. Since the beginning of the 2010s, however, a reversal in trend seems to be observed in all regions except in sub-Saharan Africa,where the informal economyculminates at the highest level: 73.8% in 2010-14, due to the sharp increase in Western Africa (81.1%).

Table 1: Employment in the informal economy in % of non-agricultural employment by 5-year periods in various regions and sub-regions.

|

Source: Charmes Jacques (2012) ‘The informal economy worldwide: trends and characteristics’, Margin—The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 6:2 (2012): 103–132, updated with new countries.

Note: Figures in italics are based on a too small number of countries to be representative

|

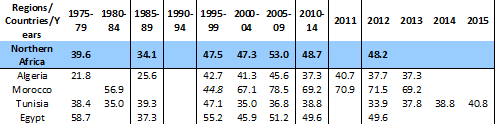

Northern Africa (table 2), the region where estimates are the most numerous over all fourdecades, can be taken as an illustration of the counter-cyclical behaviour of employment in the informal economy: it increases when the rate of economic growth is decelerating, and contracts when the rate of growth increases. Tunisia is a good example, starting from a relatively high level (38.4% of total non-agricultural employment), employment in the informal economy drops (down to 35%) in the mid of the 1980s when the implementation of structural adjustment programmes induces its rapid growth until the end of the 1980s (39.3%) and even until the end of the 1990s (47.1%). Then the informal economy drops dramatically (35%) in the mid of the 2000s with the rapid growth of the Tunisian economy and starts growing again until 2007 (36.8%). Surprisingly, it drops again to 33.9% in 2012, followingthe revolution of 2011, dueto the hiring of the unemployed in civil service by the new authorities, a policywhich did not last long, and after this short remissionthe informal economy appearsto initiate a more prolongedincrease. In Algeria, getting out of an administered and centralised economy, the informal economy has continuously grown up from 21.8% in the mid of the 1970s, up to 45.6% at the end of the 2000s, with a minorand short decrease (41.3%) at the beginning of the 2000s. After a new increase to 45.6% at the end of the 2000s, the authorities launched strong youth employment creation policies that can explain the long and persistent drop observed in the years following (37.3% in 2013). Morocco is also characterised by a continuous increase in the informal economy, from 56.9% at the beginning of the 1980s up to 78.5% at the end of the 2000s, initiating a decrease at the turn of 2010 (69.2% in 2013). Egypt is also experiencing counter-cyclical behaviours in the growth of the informal economy since the end of the 1990s.

On average for the region, the most recent period is characterised by a considerableincrease of employment in the informal economy, growing from 47.3% at the beginning of the 2000s to 53.0% at the end of the decade.

Table 2: Share of employment in the informal economy in total non-agricultural employment by 5-year period and by year since 2010 in Northern Africa.

Source: Charmes Jacques (2012) ‘The informal economy worldwide: trends and characteristics’, Margin—The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 6:2 (2012): 103–132, updated with new countries.

Note: Non-weighted averages. Figures in italics refer to employment in the informal sector only.

Table 3 illustrates the share of employment in the informal economy by decade in Sub-Saharan Africa in all non-agricultural employment. Itgroups Sub-Saharan Africa countries by decade in order to providemore observations for each period (17 countries during the 2000s, seven for the 1980s, and eight for the 1990s). The last decade is characterised by a numerous set of countries (17), but only five of them provided estimates for the previous periods, making it difficult to assess the trend for the region.25 countries have collected data for the last 5-year period. The figures for the region give an image of a continuously growing informal economy (from more than 60% in the 1970s to more than 70% during the following three decades), until the 2010s, which seem to be characterised by a sharp increase. Even ifthe share of employment in the informal economy at 73.8% is not representative for all countries of the region, if we compare the 16 countries for which data are available in the 2000s and for the most recent period, the rate of employment in the informal economy has increased from 70.4% to 75.1% between the two periods, or nearly fivepercentage points.

Table 3: Share of employment in the informal economy in total non-agricultural employment by decade in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Source: Charmes Jacques (2012) ‘The informal economy worldwide: trends and characteristics’, Margin—The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 6:2 (2012): 103–132, updated with new countries.

Note: Non-weighted averages. Figures in italics refer to employment in the informal sector only. Figures in italics and with * refer to employment in the informal sector and secondary activities. Figures in bold and italics mean that the average is based on a too small set of countries to be representative.

In the most recent period, employment in the informal economy ranges from 41.4% in South Africa (a country with a large base of wage-workers) to 96% in Benin and in Mauritania. In three more countries, the share of employment in the informal economy is higher than 90%(in Uganda and Madagascar). Generally, the share of employment in the informal economy seems higher in Western and Middle Africa than in Eastern and Southern Africa (table 1).

In Latin America, employment in the informal economy, which has peaked at 59% in the late 2000s, drops from 59.5% at the end of the 2000s to 57.2% in 2013. Shares in non-agricultural employment range from 30.7% in Costa Rica, 33.2% in Uruguay, 36.8% in Brazil to 68.8% in Peru, 73.4% in Honduras, 74.4% in Guatemala and 80.7% in the Dominican Republic.

Table 4: Share of employment in the informal economy in total non-agricultural employment by 5-year period and by year since 2010 in Latin America.

Source: Charmes Jacques (2012) ‘The informal economy worldwide: trends and characteristics’, Margin—The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 6:2 (2012): 103–132, updated with new countries.

Note: Non-weighted averages.

In Southern and South-Eastern Asia, employment in the informal economy is stabilised around 70% of non-agricultural employment in the mid-2000s (if the average does not include Mongolia, a country that could be more appropriately classified among the transition economies), ranging from 41.1% in Thailand to 84.2% in India and 86.4% in Nepal.

Countries of Western Asia could be classified with Northern Africa in the Middle East-North Africa region (MENA) as they present many similar characteristics, in particular low female activity rates. Their average share of employment in the informal economy is around 40-50% (43.2% in 2000-04).

Table 5: Share of employment in the informal economy in total non-agricultural employment by 5-year period in Asia.

Source: Charmes Jacques (2012) ‘The informal economy worldwide: trends and characteristics’, Margin—The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 6:2 (2012): 103–132, updated with new countries.

Note: Non-weighted averages. Figures in italics refer to informal sector employment only. (*) Without Mongolia.

Lastly, transition countries are making their way out of their former administered-centralised-wage economies. Their share of employment in the informal economy (still often measured through the concept of informal sector as in Russia and Ukraine) is incrementally increasing from 20.7% at the beginning of the 2000s, up to 25.1% at the end of the decade, with maxima in Kyrgyzstan (59.2% for the informal sector) and Azerbaijan (45.8%) and minima in Ukraine and Russia (9.4% and 12.1% respectively for the informal sector).

Table 6: Share of employment in the informal economy in total non-agricultural employment by 5-year period in transition countries.

Source: Charmes Jacques (2012) ‘The informal economy worldwide: trends and characteristics’, Margin—The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 6:2 (2012): 103–132, updated with new countries.

Note: Non-weighted averages. Figures in italics refer to informal sector employment only. (*) Without Slovakia.

Employment in the informal economy represents more than 50% of total non-agricultural employment in all developing regions with the exception ofthe latter region, which is at its starting point. With upward trends in sub-Saharan Africa, stabilised trends in Asia and slowly increasing trends elsewhere, it seems that there is a kind of convergence between the various regions at the global level.