1.4.1.1 Which partners in the Team Europe approach?

It is essential to understand the perspectives of those who influence the design and success of TEIs (and other joint actions, such as Global Gateway flagship projects), joint programming and joint implementation. Beyond the actors following a Team Europe approach who are responsible for the design and implementation, and who are accountable for results, other relevant stakeholders (referred to as partners in a Team Europe approach a) to be involved and consulted in the process include:

- national authorities of the partner country (if possible, depending on the context and the political situation);

- other development partners that operate in the same context and, while not being involved in the Team Europe approach, may have relevant views on its value and impact – these can include bilateral actors and multilateral actors like the UN, WB and other international financial institutions (IFIs);

- civil society (local, European and international organisations including, in particular, women’s and young people’s organisations);

- local authorities;

- the (local) private sector, including chambers of commerce, (associations of) small to medium sized enterprises (SMEs), sectoral associations, companies, transnational corporations, commercial banks and insurance companies, trade finance

- the European private sector, including chambers of commerce, small to medium sized enterprises (SMEs), companies, transnational corporations, commercial banks and insurance companies, trade finance, export credit agencies, etc.)

National authorities of the partner country

The European Consensus on development highlights that ‘partner country appropriation and ownership are essential’ and that joint programming should be led by the partner country’s development strategy and aligned to the partner country’s development priorities. In its 2016 conclusions on stepping up joint programming, the Council ‘encourages the EU and Member States to strengthen their efforts to raise awareness among partner governments and other stakeholders of Joint Programming to strengthen and encourage ownership and alignment by timely consultations and dialogue’. The Council conclusions on the team Europe approach from November 2023 further underline the importance of the ‘increase of local ownership, alignment, harmonisation within a Team Europe approach, results orientation, impact and mutual accountability through policy dialogue with partner countries on local, national and regional development policies and objectives, coordinated on the ground by the EU Delegations with the most inclusive possible involvement of Member States’.

The engagement of the partner country’s government in the processes of the Team Europe approach should not be taken for granted. Concerted efforts should be made to engage the partner country, especially by Heads of Mission and Cooperation, to design and offer transformative packages in support of government priorities on sectors and modalities in line with the national development plan and the respective sector strategies and reform programmes.

Experience shows that there can sometimes be reluctance on the part of the partner country in relation to the Team Europe approach because of issues such as the fear of ‘losing’ bilateral relationships or funds. This can be overcome by:

- emphasising the flexible and country-driven nature of the Team Europe approach;

- scheduling regular and timely contacts at all stages of the process, including for the preparation, implementation and follow up of JP, JI and TEIs;

- ensuring timely communication that emphasises the tailored approach and the benefits of Team Europe approach to both sides of the partnership.

Other development partners

All relevant development partners should be consulted during the Team Europe approach process to ensure that there is complementarity and synergy with their own work on a continuous basis.

When it comes to joint programming and TEIs, like-minded partners can participate at country level following a decision by Member States’ Heads of Mission. When like-minded non-EU partners join the process, if agreed locally and in accordance with general instructions, it is important to set out and agree on procedures to allow them to participate in relevant Heads of Mission discussions.

As stated in the European Consensus, joint programming is inclusive and open to all partners of the EU who agree to and can contribute to a common vision, including like-minded governments, the United Nations and other international and regional organisations and financial institutions when they are assessed to be relevant.

In some countries, similar processes carried out by other development partners, such as the preparation of the United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (UNSDCF) or the Joint Intersectoral Analysis Framework (JIAF), can also provide opportunities to share analyses and learn lessons.

Civil society

As they have progressively developed their human rights-based and multi-stakeholder approaches, the EU and Members States have assigned an increasingly important role to national and international civil society organisations (CSOs). Engaging more strategically with CSOs at global, regional and country level constitutes a key pillar of these approaches. The EU’s commitment to the mainstreaming of civil society engagement is enshrined in several policy documents, starting with the 2012 Communication ‘The Roots of democracy and sustainable development’, and the European Consensus. The 2021 Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument – Global Europe Regulation reaffirms that local, European and international CSOs should be duly consulted and have timely access to all relevant information that enables them to be adequately involved and play a meaningful role during the design, implementation and monitoring processes of programmes.

EU Delegations generally use three main approaches to consult CSOs:

- ad hoc consultations (i.e. called for when needed, to get feedback and insights from CSOs on specific policies, strategies or programmes; no follow up planned);

- regular consultations (i.e. regular – at least twice a year - but not yet institutionalised as a permanent space for dialogue; meetings planned in advance, preparation and follow-up by sharing documents and information, etc.).

- structured dialogue (i.e. permanent or institutionalised space for dialogue with clear terms of reference and a minimum number of consultation sessions contents and agenda can be discussed together in advance; regular flow of information between the parties involved, etc.).

⇒ For more information see Annex 4.4 on the key role of CSOs in the five EU external action priorities areas and the guidance note on mainstreaming civil society engagement in EU cooperation and external relations in the post-2020 phase[41].

There are a growing number of good practices involving EU civil society roadmaps[42] and the process of the Team Europe approach, which lead to a more regular and, in some cases, structured dialogue between civil society and actors following a Team Europe approach. The two processes can benefit from closer coordination as the roadmaps can offer deeper insights into the issue of creating a space for CSOs (i.e. an enabling environment), while also offering avenues to deepen dialogue with and streamline support to CSOs. EU Delegations are therefore encouraged to find synergies between the two processes in a manner that is adapted to their country’s context.

The EU civil society roadmaps

EU civil society roadmaps were introduced in 2012 to improve the impact, predictability and visibility of EU actions, and to ensure consistency and synergy of support to CSOs in the various sectors covered by EU external relations. They are intended to progressively stimulate coordination and the sharing of best practices with EU Member States and, possibly, with other like-minded international actors active in supporting CSOs. Roadmaps are country-specific and driven by local knowledge. They are planned, designed, implemented and followed up at the country level, with the EU Delegations and Member States remaining ‘in the driving seat’. They can be public or confidential in nature.

Since mid-2014, more than 115 EU Delegations have developed civil society roadmaps in close coordination with EU Member States. Delegations are currently developing the third generation of roadmaps, post- 2020. By September 2023, 92 roadmaps had been approved and were being implemented. EU civil society roadmaps are agreed in a separate local process by the EU Delegation and Member States (and they are also annexed to the human rights and democracy strategies at country level). Since 2017, there has also been a significant effort to integrate civil society roadmaps as part of the joint programming documents.

These synergies could include joint consultations or joint reviews to use resources more efficiently and ensure clear communication on EU and Member State interests and action, thus avoiding consultation fatigue among civil society partners. Also, a joint consultation process could be broader and more ambitious, and ensure a better involvement of civil society in joint programming, TEIs and joint implementation. At the same time, care must be taken to maintain the visibility that both the EU civil society roadmaps and Team Europe approaches have gained in recent years, including in partner countries.

Local authorities

In recent decades, the EU’s external policy documents have increasingly recognised the important role that local authorities play in both governance and development42. Local authorities have a crucial function in driving grassroots development thanks to their close proximity to communities, their decision-making functions, and local knowledge.

For Team Europe Initiatives, joint programming and joint implementation focusing on the local level and/or on issues which fall under the prerogative of local authorities, according to partner country’s level of political and administrative decentralisation, it will be appropriate to engage with local governments.

Engaging with local authorities can be done through their apex institutions (i.e. a national association or federation of local authorities). If so, national associations of local authorities should systematically be part of political discussions in order to voice citizens’ needs and expectations. In addition to that, it may also be of interest to approach certain local authorities individually – in particular those in charge of areas with particularly large or important constituencies (e.g. the mayor of the country’s capital or areas where actors following a Team Europe approach are particularly present – TEI mappings can be used as a tool to identify such areas).

The private sector (EU and local)

Private sector engagement in development cooperation and mutually beneficial international partnerships is a strategic priority for the EU, considering the role it can play in bringing investments, knowledge, skills and jobs to partner countries, in the current context of public finance scarcity. Furthermore, the private sector is also an active constituency of the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation. Both the Agenda 2030 and the Busan partnership agreement recognises the central role of the private sector, as well as the benefits of development finance modalities such as public-private partnerships in advancing innovation, creating wealth, income and jobs, facilitating access to domestic resources, and, in turn, contributing to poverty reduction and fostering sustainable development.

Meaningful and goal-oriented dialogue with the private sector in a Team Europe approach is important, and includes exploring opportunities to combine public, DFI and private capital. The EU supports local private sector development in partner countries, but the engagement of EU businesses is also key for channeling private funds in partner countries.

|

A stronger role of the private sector The Commission Communication ‘A Stronger Role of the Private Sector in Achieving Inclusive and Sustainable Growth in Developing Countries’ (2014)[44] placed the private sector at the forefront of international development. The communication sets out principles, criteria, support, mainstreaming and tools and methods for EU engagement with private sector in development cooperation. It also highlights that ‘[t]hrough better development partner coordination and joint programming, the EU will speak with one voice, and can better capitalise on the fact that in most partner countries it is one of the largest development partners providing support for inclusive and sustainable economic development’. |

The private sector is an important partner in a Team Europe approach, not least for the implementation of the Global Gateway strategy, which actively seeks to crowd-in private sector finance, and expertise and to involve private sector partners more closely in project origination.

The objectives of engagement with the private sector are threefold: (i) to understand business constraints for local and EU businesses wishing to internationalise or already active in partner countries and set up dialogue with partner countries to improve the business environment and investment climate; (ii) to facilitate sustainable investments; and (iii) to create decent jobs, facilitate trade and sustainable growth in partner countries.

In line with Commissioner Síkela’s mandate to take Global Gateway from start up to scale up - private sector engagement is shifting from downstream consultation to upstream co-design.

To support this shift, the EU Member States have begun establishing coordination platforms, referred to as Team Nationals. Although differing in their individual set-ups, these platforms aim to foster structured, whole-of-government dialogue between public institutions and national private sector actors interested in investing in partner countries.

Team Nationals typically bring together relevant ministries (e.g. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Industry, Economy, Development), national DFIs, implementing agencies, Member States’ ECAs, and business associations. In some cases, Trade and Investment Promotion Organisations (TPOs) are also involved. By ensuring early and continuous engagement between the national public and private sector— from project origination to implementation — Team Nationals play a key role in promoting public- private partnerships and supporting national companies entrance into partner countries’ emerging markets.

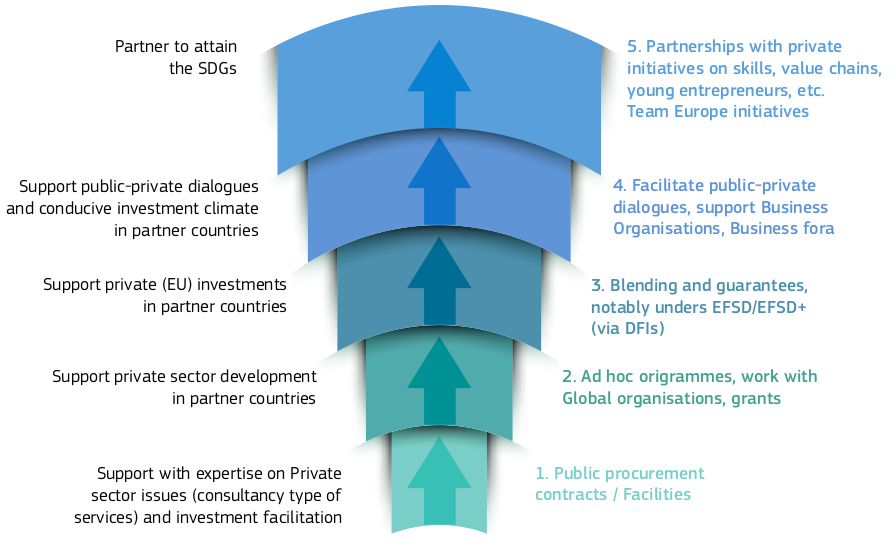

See in Figure 4, an overview of the different possible levels of engagement with the private sector via EU actions, which could serve as a starting point for a wider engagement of actors following a Team Europe approach.

See in figure 3, an overview of the different possible levels of engagement with the private sector via EU actions, which could serve as a starting point for a wider engagement of actors following a Team Europe approach.

41 Mainstreaming Civil Society engagement in European Union cooperation and external relations in the post-2020 phase – Guidance: note /library/mainstreaming-civil-society-engagement-eu-cooperation-and-external-relations-post-2020-phase_en

42 https://capacity4dev.europa.eu/groups/public-governance-civilsociety

43 The Commission Communication ‘Local Authorities: actors of development’ COM(2008) 626 final; the Commission Communication on ‘Empowering local authorities in partner countries for enhanced governance and more effective development outcomes’ COM(2013) 280 final and the corresponding Council conclusions; the Staff Working Document ‘European Union (EU) cooperation with cities and local authorities in third countries’ SWD(2018) 269 final and the corresponding Council conclusions.

44 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2014:263:FIN